【论著】| 行电视胸腔镜辅助手术的老年食管癌患者心血管不良反应发生风险的影响因素及列线图模型构建

时间:2023-09-22 11:10:44 热度:37.1℃ 作者:网络

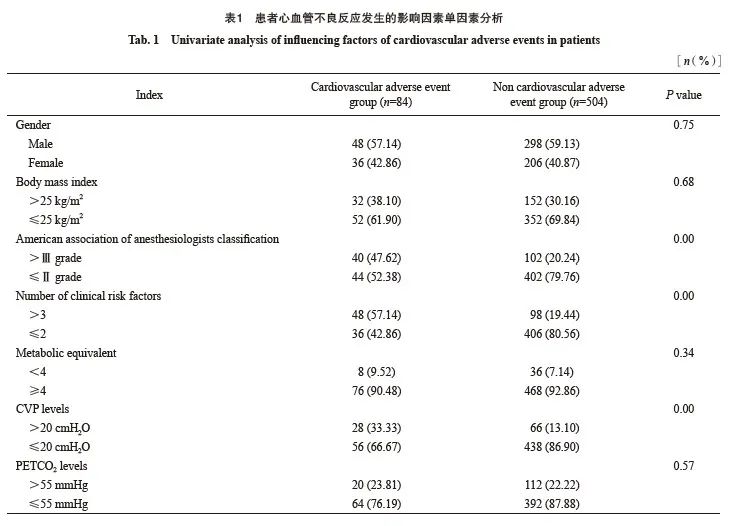

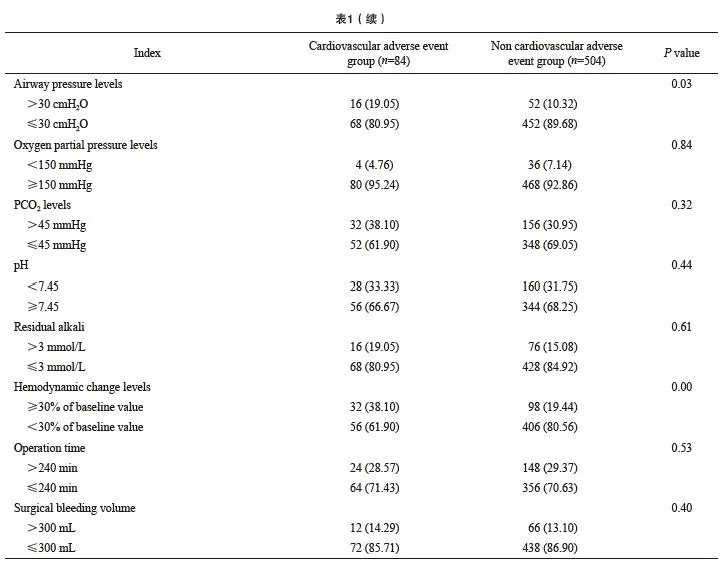

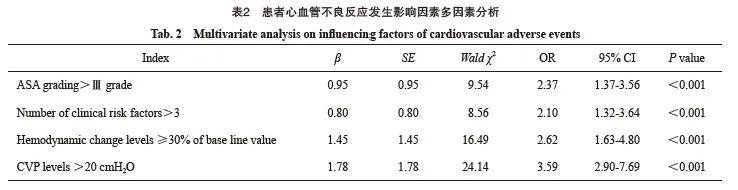

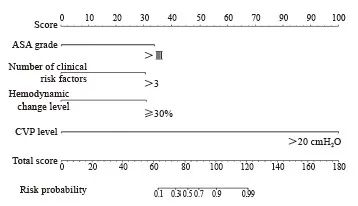

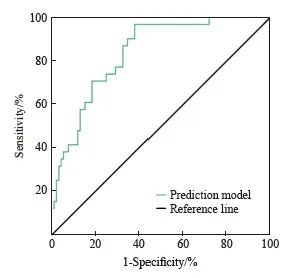

[摘要] 背景与目的:电视胸腔镜手术中人工气胸的建立可能影响胸内压,使上腔静脉回流受阻,并导致住院期间心血管不良反应发生风险升高;而老年食管癌患者因机能状态显著下降,在围手术期更易发生心血管不良反应,严重影响康复进程。本研究通过探讨行电视胸腔镜辅助手术的老年食管癌患者心血管不良反应发生风险的影响因素,并构建列线图模型,旨在为后续心血管不良反应预防及临床早期干预提供更多参考。方法:回顾性纳入2015年1月—2020年10月丹江口市第一医院收治的行电视胸腔镜辅助手术的老年食管癌患者共546例,根据围手术期是否发生心血管不良反应分组,分析相关临床资料,采用logistic回归模型评价患者心血管不良反应发生的独立影响因素,基于上述因素构建列线图预测模型,描绘受试者工作特征(receiver operating characteristic,ROC)曲线评价模型的预测效能。结果:546例患者中围手术期心血管不良反应共发生84例(15.38%)。单因素分析结果显示,美国麻醉医师协会(American Society of Anesthesiologists,ASA)分级、临床危险因素数量、血流动力学变化水平、气道压水平及中心静脉压(central venous pressure,CVP)水平均与患者心血管不良反应发生有关(P<0.05);多因素分析结果显示,ASA分级、临床危险因素数量、血流动力学变化水平及CVP水平均是患者心血管不良反应发生的独立影响因素(P<0.05)。根据多因素分析证实心血管不良反应发生风险的独立影响因素构建列线图预测模型,描绘ROC曲线评价上述列线图模型用于患者心血管不良反应发生风险预测的曲线下面积(area under curve,AUC)为0.88(95% CI:0.81~0.97),灵敏度和特异度分别为87.26%和91.60%。结论:行电视胸腔镜辅助手术的老年食管癌患者多种因素与其心血管不良反应发生独立相关,其中ASA分级>Ⅲ级、临床危险因素数量>3个、血流动力学变化水平≥30%基础值、气道压水平>30 cm H2O及CVP水平>20 cm H2O人群发生风险更高;基于上述因素构建列线图模型具有良好的预测效能,可指导临床干预方案的制定。

[关键词] 电视胸腔镜;手术;老年;食管癌;心血管不良反应;影响因素

[Abstract]Background and purpose: The establishment of artificial pneumothorax during video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery may affect the intrathoracic pressure, cause the obstruction of superior vena cava reflux, and lead to the increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events during hospitalization. However, elderly patients with esophageal cancer are more likely to have adverse cardiovascular events during the perioperative period due to the significant decline in functional status, which seriously affects the rehabilitation process. This study aimed to investigate the influencing factors of cardiovascular adverse events risk in elderly patients with esophageal cancer undergoing video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery and construct nomograph model to guide the formulation of clinical intervention plan. Methods: Five hundred and forty-six elderly patients with esophageal cancer undergoing video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery who were treated in The First Hospital of Danjiangkou City were retrospectively chosen in the period from January 2015 to October 2020. All patients were grouped according to the occurrence of cardiovascular adverse events in perioperative period, the related clinical data were analyzed, and the independent influencing factors of cardiovascular adverse events were evaluated by logistic regression model. Based on the above factors, the nomogram prediction model was constructed and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was drawn to evaluate the prediction efficiency of nomogram model. Results: Eighty-four cases (15.38%) had perioperative cardiovascular adverse events in all 546 patients. Univariate analysis showed that American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade, the number of clinical risk factors, the level of hemodynamic changes, the level of airway pressure and the level of central venous pressure (CVP) were all related to the occurrence of cardiovascular adverse events (P<0.05). Multivariate analysis showed that ASA classification, the number of clinical risk factors, the level of hemodynamic changes and CVP were the independent influencing factors of cardiovascular adverse events (P<0.05). The nomogram prediction model was constructed according to the independent influencing factors of cardiovascular adverse event risk confirmed by multivariate analysis. The area under curve (AUC) of above nomogram model for predicting the risk of cardiovascular adverse events was 0.88 (95% CI: 0.81-0.97), and the sensitivity and specificity were 87.26% and 91.60% respectively. Conclusion: The incidence of cardiovascular adverse events in elderly patients with esophageal cancer undergoing video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery is independently related to many factors, of which ASA grade >Ⅲ, number of clinical risk factors >3, hemodynamic change level ≥30%, airway pressure level >30 cm H2O and CVP level >20 cm H2O have higher risk. The nomogram model based on the above factors has good prediction efficiency and may guide the formulation of clinical intervention programs.

[Key words] Video-assisted thoracoscopic; Surgery; Elderly; Esophageal cancer; Cardiovascular adverse events; Influencing factors

电视胸腔镜近年来以其微创、术后肺功能恢复快及并发症少等优势,已成为食管癌治疗的首选方案[1]。电视胸腔镜手术过程中往往需建立人工气胸,会导致胸内压短时间内显著升高,上腔静脉回流受阻,严重者还可导致纵隔移位、高碳酸血症或心脏压迫;同时这也是诱发住院期间心血管不良反应发生的关键因素[2-3]。老年食管癌患者因机能状态尤其是心肺代偿能力下降且往往存在多种基础疾病,围手术期更易发生心血管不良反应,严重影响康复进程[4]。本研究旨在探讨行电视胸腔镜辅助手术的老年食管癌患者心血管不良反应发生风险的影响因素,并构建列线图模型,为后续心血管不良反应的预防及临床早期干预提供更多参考。

1 资料和方法

1.1 研究对象

回顾性纳入丹江口市第一医院2015年1月—2020年10月收治的行电视胸腔镜辅助手术的老年食管癌患者共546例。纳入标准:① 经病理组织学检查确诊食管癌[5];② 年龄≥65岁;③ 顺利完成电视胸腔镜辅助手术;④ 基线及随访资料完整。排除标准:① 存在急性心脑血管疾病;② 术中改开胸手术;③ 存在手术或麻醉禁忌证;④ 术中未采用人工气胸;⑤ 不愿配合检查随访。研究设计符合《赫尔辛基宣言》要求。

1.2 手术方法

全身麻醉下将单腔或双腔气管导管置入,确定定位良好后连接呼吸机,单腔导管直接建立人工气胸;人工气胸建立采用CO2吹入法,速率2~3 L/min,胸内压位置在5~10 mmHg,促进患肺萎陷以保证良好术野。潮气量、心率(heart rate,HR)、吸入氧浓度分数分别设置为6~8 mL/kg、15~18次/min、60%~80%;桡动脉穿刺测压,右颈内静脉穿刺检测中心静脉压(central venous pressure,CVP),最后行血气分析检查。术中动态监测HR、平均动脉压(mean arterial pressure,MAP)、CVP、脉搏血氧饱和度(saturation of pulse oximetry,SpO2)、呼气末CO2分压(partial end-expiratory CO2 pressure,PETCO2)、气道压、胸内压及血气分析指标,同时记录手术时间和手术出血量。

1.3 观察指标

查阅病例记录年龄、性别、身高、体重、心血管疾病发生情况、临床相关因素、代谢当量、生命体征指标、手术用时及手术出血量等资料;临床危险因素评估的具体指标包括心肌梗死、心绞痛、心力衰竭、心律失常、心脏瓣膜疾病、肾功能不全、糖尿病、年龄≥70岁、活动能力受限、中风史及无法控制的高血压。采用电话或病例查阅方式完成随访,随访终点为住院期间出现手术相关心血管不良反应,具体包括恶性心律失常、心肌缺血、室颤及急性心衰。

1.4 统计学处理

采用SPSS 20.0软件对数据进行处理,数据描述采用频数和百分比(%)表示,单因素分析采用χ2检验或确切概率法,将单因素分析差异有统计学意义的指标纳入logistic回归模型进行多因素分析,列线图模型拟合优度应用Hosmer‐Lemeshow检验进行评估,利用受试者工作特征(receiver operating characteristic,ROC)曲线评估模型的预测效能。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结 果

2.1 围手术期心血管不良反应的发生情况

546例患者中围手术期心血管不良反应共发生84例(15.38%),其中恶性心律失常22例,心肌缺血18例,急性心衰2例。

2.2 患者心血管不良反应发生的影响因素单因素分析

单因素分析结果显示,美国麻醉医师协会(American Society of Anesthesiologists,ASA)分级、临床危险因素数量、血流动力学变化水平、气道压水平及CVP水平均与患者心血管不良反应的发生有关(P<0.05,表1)。

2.3 患者心血管不良反应发生的影响因素多因素分析

多因素分析结果显示,美国麻醉医师协会(American Society of Anesthesiologists,ASA)分级、临床危险因素数量、血流动力学变化水平及CVP水平均是患者心血管不良反应发生的独立影响因素(P <0.05,表2)。

2.4 患者心血管不良反应发生风险的列线图预测模型构建及预测效能ROC曲线分析

根据多因素分析证实心血管不良反应发生风险的独立影响因素构建列线图预测模型(图1),ASA分级>Ⅲ级、临床危险因素数量>3个、血流动力学变化水平≥30%基础值、CVP水平>20 cmH2O分别赋值为33、30、30、100,模型拟合优度偏置校正C指数为0.87;描绘ROC曲线评价上述列线图模型用于患者心血管不良反应的发生风险预测曲线下面积(area under curve,AUC)为0.88(95% CI:0.81~0.97),灵敏度和特异度分别为87.26%和91.60%(图2)。

图1 心血管不良反应发生风险列线图

Fig. 1 Nomograph of cardiovascular adverse events risk

图2 患者心血管不良反应发生风险列线图预测效能ROC曲线分析

Fig. 2 ROC curve of predictive efficacy in nomograph of cardiovascular adverse event risk

3 讨 论

电视胸腔镜手术与传统开胸手术相比,可保证胸廓完整性,不切断肌肉和肋骨,手术创伤程度明显下降,且术后恢复时间更短[6]。电视胸腔镜手术通气和术野暴露目前仍依靠双腔导管单肺通气或单腔插管人工气胸,有研究[7]证实,单腔插管下电视胸腔镜辅助食管癌根治术具有肺萎陷效果佳、术野暴露彻底、淋巴结清扫彻底及可避免喉返神经损伤等优势,而双腔插管因管径较粗大且过硬,较易导致淋巴结清扫不彻底。但单腔导管需通过CO2吹入法建立人工气胸,易影响机体呼吸及循环系统[8]。有研究[9]显示,单肺或双肺通气下胸腔内压如超过5 mmHg,则可反应性刺激CVP、MPAP及PCWP水平升高,同时影响HR和MAP水平,随着胸膜腔正压升高,上述改变更为明显。此外胸腔内压升高还可导致循环系统衰竭、恶性心律失常或对侧气胸,严重影响手术效果,威胁生命安全。

以往有关胸腔镜下交感神经切断术的研究[10]发现,患者围手术期CVP、MPAP及PCWP水平仅轻微升高,均未引起需干预的循环障碍。另一项研究[5]亦证实,CO2人工气胸建立后患者HR、CVP及PCO2水平均可见升高趋势,pH则显著下降,在30 min后稳定,并在停止充气5~10 min后恢复至正常水平。但以上研究手术充气时间均不足90 min,而对于操作复杂和耗时更长的食管癌电视胸腔镜手术仍需进一步研究验证。

ASA分级是评估患者病情及手术预后的常用指标之一,评价方法简单,能够反映基本病情的严重程度,但缺少手术风险分层及其他可能的影响因素[11];目前认为ASA分级Ⅲ级以上患者病情危重、体力受限明显,仅能完成日常活动。已有研究[12]显示,ASA分级Ⅲ级以上患者住院期间死亡率可达2%~5%。美国心脏协会和美国心脏病学会针对非心脏手术围手术期处理指南[13]所指定评估标准包含年龄、代谢当量、合并慢性病及手术风险等指标,其中存在3个及以上临床风险因素者更易在住院期间发生心血管不良反应。本研究结果证实,ASA分级>Ⅲ级和临床危险因素>3个均与患者心血管不良反应发生独立相关;同时我们注意到临床风险因素>3个的患者心血管不良反应发生率较ASA分级≥Ⅲ级更高,造成这一现象的可能原因为不同临床风险因素分层间的权重差异。

目前反映血流动力学的指标众多,本次研究纳入指标包括血压、HR、CVP及血流动力学变化情况,而多因素分析结果证实,血流动力学变化水平和CVP水平与患者住院期间心血管不良反应发生独立相关,基于以上证据,我们认为应加强围手术期CVP监测,最大限度稳定血流动力学。Nakajima等[14]研究证实,CVP可真实反映患者的胸内压变化和心脏压迫情况,考虑到手术部位和麻醉通气模式干扰,这一指标水平更为敏感。此外血流动力学指标变化水平过大已被证实能够增加心肌耗氧量,影响血管剪切力,诱发陈旧性附壁血栓脱落栓塞;老年人群因普遍存在血管壁硬化和心肺代偿功能降低的问题,对于血流动力学变化更为敏感,对于机体影响亦更为严重[15]。

本研究根据多因素分析证实心血管不良反应发生风险的独立影响因素构建列线图预测模型,而这一列线图模型用于患者心血管不良反应的发生风险预测AUC为0.88(95% CI:0.81~0.97),灵敏度和特异度分别为87.26%和91.60%,显示出良好的预测效能;考虑到模型中指标均简单易得,故具有一定临床应用价值,可为临床个性化干预方案的制订提供参考。

本研究亦存在一定不足:① 属于单中心回顾性研究,无法完全排除混杂因素影响;② 纳入观察指标相对较少,仍有待后续更为全面深入研究验证。

综上所述,行电视胸腔镜辅助手术的老年食管癌患者心血管不良反应发生与多种因素独立相关,其中ASA分级>Ⅲ级、临床危险因素数量>3个、血流动力学变化水平≥30%基础值、气道压水平>30 cmH2O及CVP水平>20 cmH2O人群发生风险更高;基于上述因素构建列线图模型具有良好的预测效能,可指导临床干预方案的制订。

利益冲突声明:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

[参考文献]

[1] OHI M, TOIYAMA Y, OMURA Y, et al. Risk factors and measures of pulmonary complications after thoracoscopic esophagectomy for esophageal cancer[J]. Surg Today, 2019, 49(2): 176-186.

[2] NACHIRA D, MEACCI E, MASTROMARINO M G, et al. Initial experience with uniportal video-assisted thoracic surgery esophagectomy[J]. J Thorac Dis, 2018, 10(Suppl 31): S3686-S3695.

[3] SCHMIDT H M, GISBERTZ S S, MOONS J, et al. Defining benchmarks for transthoracic esophagectomy: a multicenter analysis of total minimally invasive esophagectomy in low risk patients[J]. Ann Surg, 2017, 266(5): 814-821.

[4] ALDERSON D, CUNNINGHAM D, NANKIVELL M, et al. Neoadjuvant cisplatin and fluorouracil versus epirubicin, cisplatin, and capecitabine followed by rep in patients with oesophageal adenocarcinoma (UK MRC OE05): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2017, 18(9): 1249-1260.

[5] CHEN J Y, LIU Q W, ZHANG X, et al. Comparisons of shortterm outcomes between robot-assisted and thoraco-laparoscopic esophagectomy with extended two-field lymph node disp for resectable thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma[J]. J Thorac Dis, 2019, 11(9): 3874-3880.

[6] JIN D C, YAO L, YU J, et al. Robotic-assisted minimally invasive esophagectomy versus the conventional minimally invasive one: a meta-analysis and systematic review[J]. Int J Med Robot, 2019, 15(3): e1988.

[7] CHAO Y K, WEN Y W, CHUANG W Y, et al. Transition from video-assisted thoracoscopic to robotic esophagectomy: a single surgeon's experience[J]. Dis Esophagus, 2020, 33(2): doz033.

[8] CHAO Y K, LI Z G, WEN Y W, et al. Robotic-assisted Esophagectomy vs Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Esophagectomy (REVATE): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial[J]. Trials, 2019, 20(1): 346.

[9] CHAI T C, SHEN Z M, CHEN S, et al. Right versus left thoracic approach oesophagectomy for oesophageal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol[J]. BMJ Open, 2019, 9(7): e030157.

[10] HAYASHI M, TAKEUCHI H, NAKAMURA R, et al. Determination of the optimal surgical procedure by identifying risk factors for pneumonia after transthoracic esophagectomy[J]. Esophagus, 2020, 17(1): 50-58.

[11] SALEM A I, THAU M R, STROM T J, et al. Effect of body mass index on operative outcome after robotic-assisted Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy: retrospective analysis of 129 cases at a single high-volume tertiary care center[J]. Dis Esophagus, 2017, 30(1): 1-7.

[12] HUANG L Y, CHEN C, LIN M Q, et al. Understanding the pattern of lymph node metastasis for trans-segmental thoracic esophageal cancer to develop precise delineation of clinical target volume for radiotherapy[J]. Ann Palliat Med, 2020, 9(3): 788-794.

[13] AKIYAMA Y, SASAKI A, ENDO F, et al. Outcomes of esophagectomy after chemotherapy with biweekly docetaxel plus cisplatin and fluorouracil for advanced esophageal cancer: a retrospective cohort analysis[J]. World J Surg Oncol, 2018, 16(1): 122.

[14] NAKAJIMA M, MUROI H, KIKUCHI M, et al. Salvage esophagectomy combined with partial aortic wall rep following thoracic endovascular aortic repair[J]. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 2018, 66(12): 736-743.

[15] HAISLEY K R, ABDELMOATY W F, DUNST C M. Laparoscopic transhiatal esophagectomy for invasive esophageal adenocarcinoma[J]. J Gastrointest Surg, 2021, 25(1): 9-15.