【协和医学杂志】正确理解和应用低质量证据形成指南推荐意见

时间:2024-07-15 19:03:33 热度:37.1℃ 作者:网络

虽然临床实践指南(下文简称“指南”)的质量在过去30年间稳步提升[1-3],但制订者对其原理和方法的理解仍存在误区。其中之一为低质量证据、强推荐级别以及高质量指南之间的关系。本文以推荐分级的评估、制订与评价(GRADE)分级系统为切入点[4],阐述低质量证据的基本内涵和临床作用,介绍基于低质量证据形成指南推荐意见的方法,以期为我国指南制订者和使用者提供参考。

1 关于低质量证据的正确理解

1.1 低质量证据是指证据体的质量“低”,其中也可能包含若干高质量的原始研究

指南的新定义要求推荐意见必须基于系统评价的证据[1]。该定义表明,对于某一具体的临床问题,指南应尽可能全面检索和收集符合纳入标准的所有原始研究(primary study),并进行严格评价、综合和分析后基于证据综合(evidence synthesize)得出结论。因不同研究者针对同一临床问题所开展的研究,可能因设计和实施存在差异而产生不同,甚至矛盾的结果。若仅基于单个研究进行临床实践,可能作出有偏倚甚至弊大于利的临床决策[5]。因此,本文所说的证据,特指系统检索后能够回答某一临床问题的所有符合标准的研究,其被视为一个整体,称为“证据体或证据群(body of evidence)”,通常采用GRADE分级系统评估其质量。

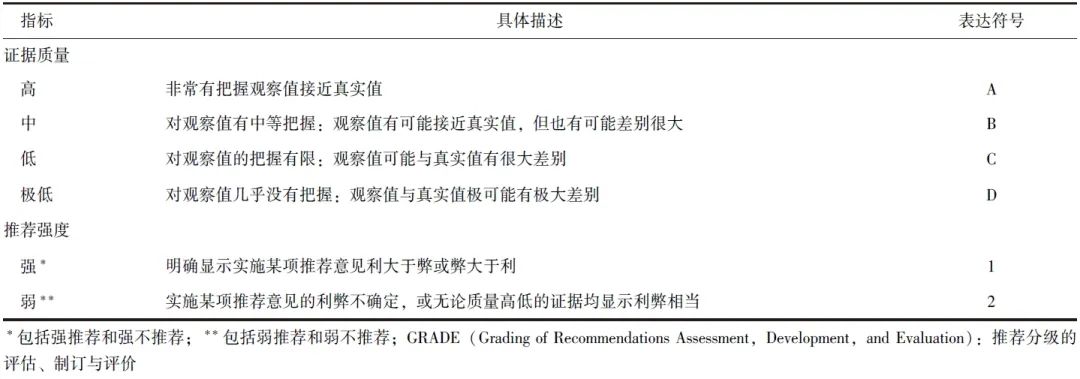

在GRADE分级系统中,证据质量(quality of evidence)被定义为“对观察值的真实性有多大把握”[4]。对于某一具体临床问题,当研究被系统检索和汇总后,可基于5个降级因素和3个升级因素将证据体质量分为高、中、低、极低4个等级(表1)[6-7]。

表1 GRADE分级系统中证据质量与推荐强度的含义[4,6]

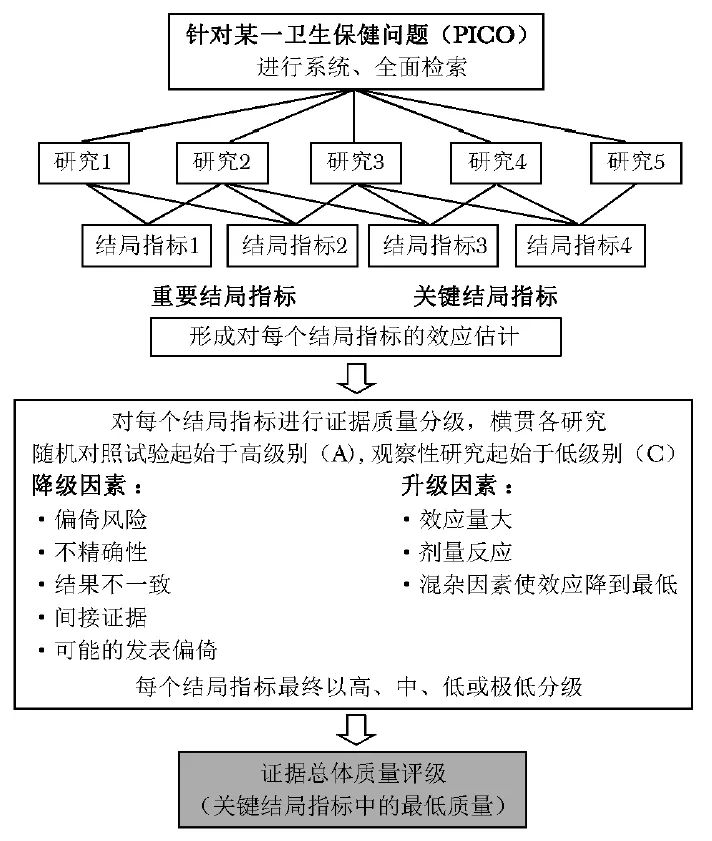

为便于理解和应用,本文将GRADE分级系统中的C级(低)和D级(极低)证据,均归类为“低质量证据”。在证据分级的过程中,指南制订者容易将证据质量与原始研究本身的质量混淆,但后者只是影响证据质量的因素之一,GRADE手册将其称为研究的局限性或偏倚风险(图1)[8]。

图1 应用GRADE分级系统评估某一临床问题中不同结局指标的证据体质量[7]

PICO:研究对象,干预措施,对照或比较措施,结局指标;GRADE:同表1

在进行证据分级时还需考虑研究结果的不精确性、不一致性和间接性,以及发表偏倚等[7-8]。以“瑞德西韦能否有效治疗COVID-19”为例,1篇发表于Lancet Respir Med 的系统评价最终纳入9篇随机对照试验研究进行分析[9],其中部分单个研究的质量很高或偏倚风险很低[10-11]。但汇总分析结果显示,因研究总体估计效应的精确度显著不足,对于接受通气治疗的住院患者,瑞德西韦能否降低病死率仍存在较大的不确定性(对应GRADE分级系统中的C级证据)。

1.2 低质量证据也是当前可得的最佳证据

仍以上文“瑞德西韦能否有效治疗COVID-19”为例,尽管瑞德西韦在降低需接受通气治疗的COVID-19患者病死率方面的证据质量为“低”,但相对于单个研究或专家经验而言,其仍属于当前可得的“最佳”证据,可为决策者提供重要的判断依据。类似情况还存在于某些经常被临床研究排除的特殊群体(如儿童、孕产妇或老年患者)、罕见病患者,以及其他无法开展随机对照试验的情况[12-13]。

针对此类人群开展的临床研究,进行系统评价后所得到的结果,尽管使用GRADE分级系统有可能判断为低或极低质量证据,其依旧是当前可获得的最佳证据,能够为指南和临床实践提供重要信息[14]。另一种情况可见于突发公共卫生事件,如COVID-19疫情初期,专家需在短时间内作出决策。彼时直接证据匮乏,但仍可借鉴间接证据开展决策。

譬如《国际儿童COVID-19管理快速建议指南》[15],结合严重急性呼吸综合征(SARS)、中东呼吸综合征(MERS)和流感的间接证据,制作了快速系统评价,就儿童COVID-19患者的临床表现、筛查、治疗、母乳喂养、健康教育等方面给出了10条具体推荐意见,其中8条基于低或极低质量证据。

同样,2018年Lancet 发表的《埃博拉病毒病患者支持治疗的循证指南》[16],在系统检索文献的基础上,结合与埃博拉病毒病相似的其他疾病证据(如休克、霍乱、败血症和其他严重腹泻疾病),指南制订小组共形成了8条推荐意见,其中3条基于低质量证据,4条基于中等质量证据,仅1条基于高质量证据。

1.3 低质量证据在证据谱中占主要比例

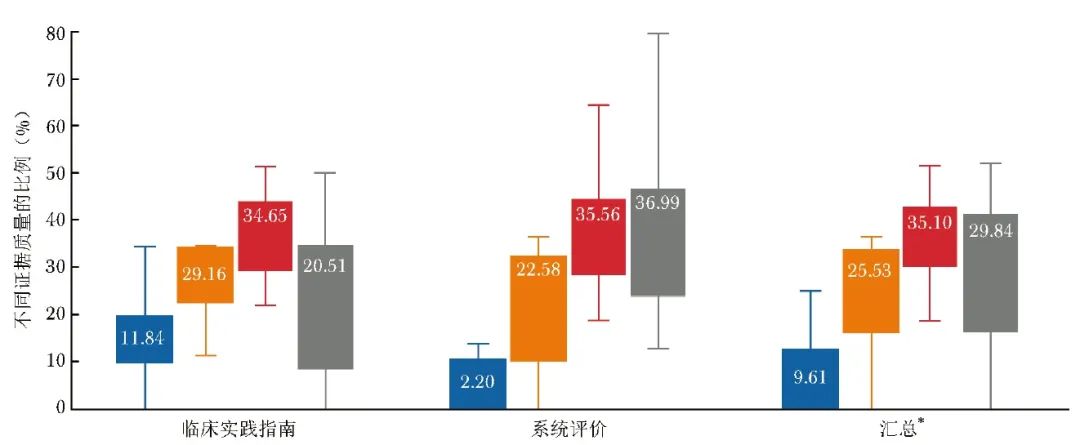

相关研究基于GRADE分级系统分析了已发表指南和系统评价中的证据质量,笔者检索了MEDLINE数据库,对其进行初步汇总。检索策略为(“systematic review*”[Title] OR “meta-analys*”[Title] OR “meta analys*”[Title] OR “guideline*”[Title] OR “recommendation*”[Title]) AND (“certainty”[Title] OR “confidence”[Title] OR (“evidence”[Title] AND (“quality”[Title] OR “level”[Title] OR “levels*”[Title] OR “underlying”[Title] OR “strength”[Title] OR “behind”[Title])))。检索时间为建库至2024年4月30日,共获取22篇相关研究[17-38]。结果显示,低(C级)和极低(D级)质量证据在证据谱中占主要比例(图2)。

图2 临床实践指南和系统评价中不同证据质量的比例

注:图中标记的具体数据表示中位数;蓝色代表高质量证据(A级),橙色代表中等质量证据(B级),红色代表低质量证据(C级),灰色代表极低质量证据(D级);*包括临床实践指南和系统评价

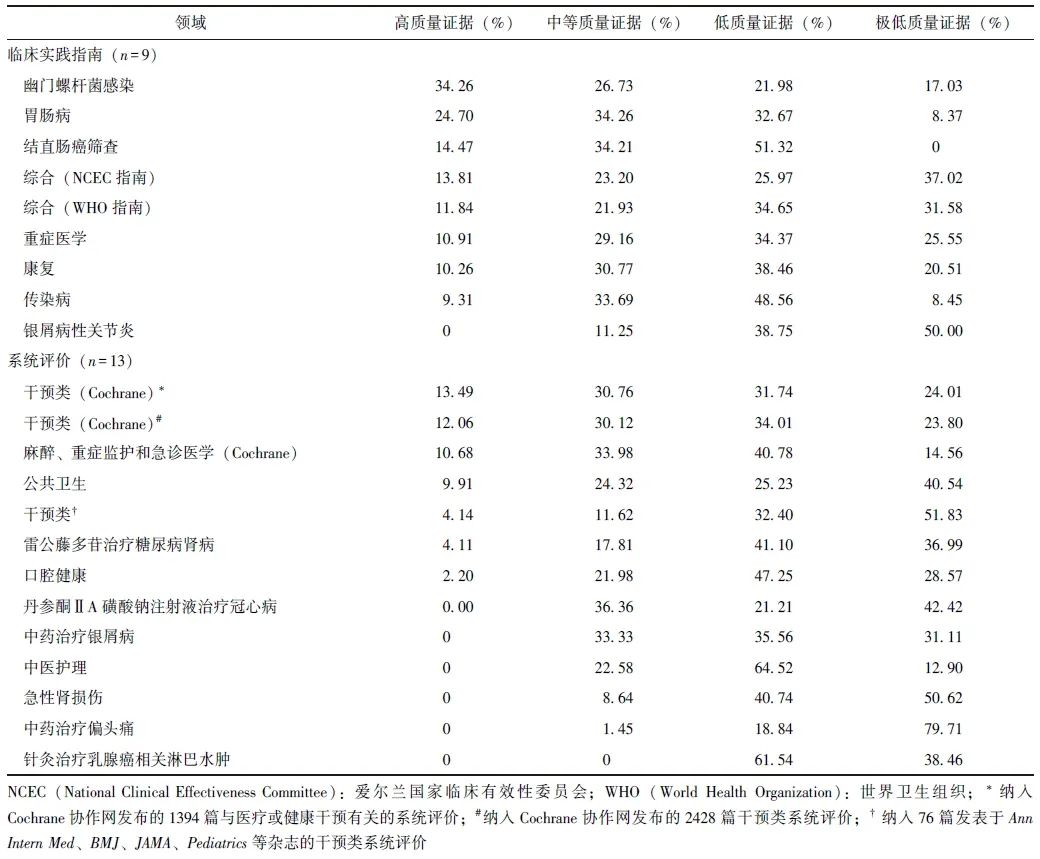

表2呈现了各领域指南和系统评价中不同证据质量的详细情况。

表2 各领域临床实践指南和系统评价中不同证据质量的比例[17-38]

1.4 低质量证据与高质量指南之间并无直接关系

在指南制订的过程中,医务人员普遍存在一个误区,即如果大部分推荐意见的支持证据都是低质量的,是否会对指南质量产生影响。事实上,指南质量的高低与其纳入的证据质量并无直接关系[14]。目前国际上公认的指南方法学质量评价工具AGREE Ⅱ(appraisal of guidelines research and evaluation Ⅱ)和指南报告质量评价工具RIGHT(reporting items for practice guidelines in healthcare)[39-40],以及2022年推出的指南科学性、透明性和适用性评级工具STAR(scientific,transparent and applicable rankings tools for clinical practice guidelines)[41],均无评价标准要求指南必须纳入高质量的研究证据,即指南纳入证据质量的高低与指南本身的质量不相关。

而在指南中详细说明采用何种方法检索和评估证据质量,并呈现具体的分级结果,才是重要的评分项。然而这一点却常被指南制订者忽略,应用GRADE分级系统评估证据质量的指南更是少之又少[42-43]。

2 基于低质量证据形成推荐意见的方法

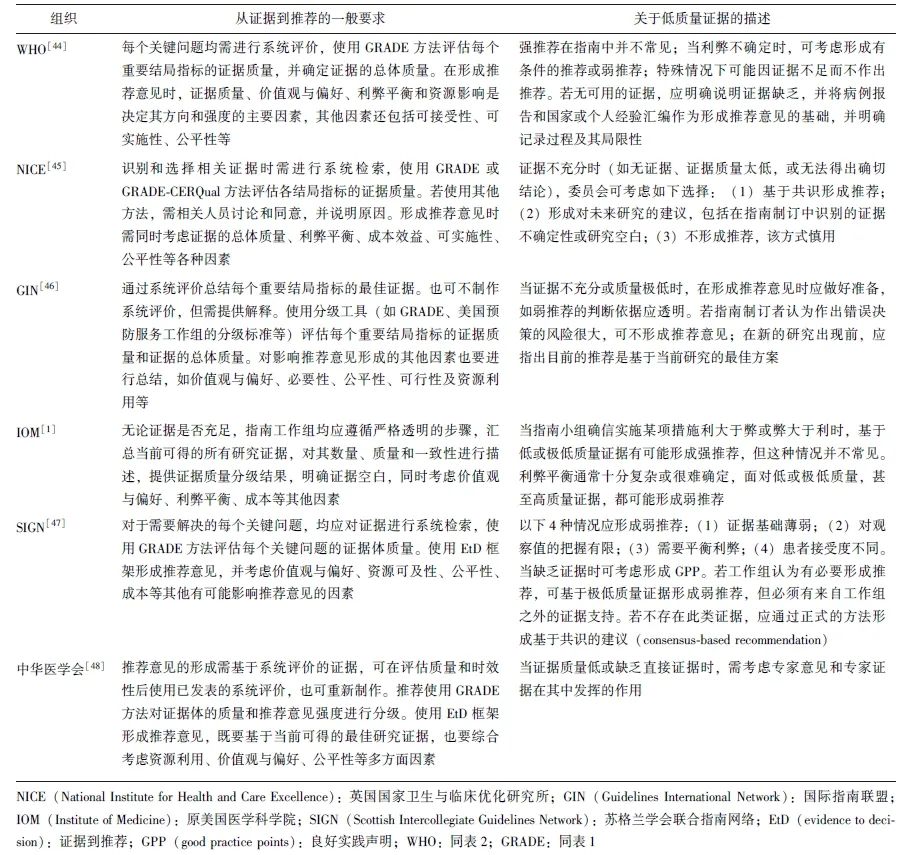

国内外不同指南制订机构就如何基于证据质量(包括低质量证据)进行推荐给出了相应的方法和建议(表3)[1,44-48]。其中,基于GRADE研发的EtD(evidence to decision)框架,因其科学的设计、透明的流程和清晰的表述,成为包括诸多国际组织在内的指南制订者形成推荐意见时参考的主要依据[49]。

表3 主要指南制订手册关于从证据到推荐的一般要求和对低质量证据的考虑

2.1 正确判断证据质量

尽管低质量证据十分常见,但在应用GRADE分级系统判断证据质量时仍需谨慎,特别注意以下两点。

1

GRADE的证据质量分级并非针对单个临床研究或系统评价,而是针对报告了某个结局指标的证据体的质量分级(图1)[4,6]。即使是同一临床问题的不同结局指标,证据质量也可能存在很大差别。

2

GRADE将结局指标分为三类:关键(critical)、重要而非关键(important but not critical)、重要性有限(limited importance)[50]。

当一项措施可同时影响多个结局指标时,该措施总体证据质量的判断取决于关键结局指标的最低证据质量[50-51]。例如,胰腺癌或壶腹周围癌患者应采用幽门保留术,还是标准的Whipple胰十二指肠切除术?针对此问题开展的系统评价最终纳入6项随机对照试验研究进行分析[52-53]。

结局指标包括围术期病死率(低质量证据,基于6项研究共490例患者)、5年病死率(中等质量证据,基于3项研究共229例患者)、胆汁渗漏(低质量证据,基于3项研究共268例患者)、胃排空延迟(极低质量证据,基于5项研究共442例患者)等。

若指南制订小组认为胃排空延迟是关键指标,则该问题的证据总体质量为“极低”;若胃排空是重要而非关键指标,围术期病死率是关键指标,则该问题的证据总体质量为“低”。GRADE分级系统的升级因素和降级因素的详细解释及进一步指导,可参考GRADE工作组发表的系列相关论文及专著[54-55]。

2.2 准确把握指南中强、弱推荐的含义

推荐强度是指遵守推荐意见对目标人群产生的利弊程度有多大把握。GRADE将其分为“强(strong)”“弱(weak)”两类[5,7],后者也可表示为“condi-tional”“discretionary”或“qualified”(表1)。

对于不同的指南使用者,强、弱推荐的具体内涵略有不同。以临床医生为例,强推荐表示应对几乎所有患者推荐该方案,弱推荐表示不同患者有各自适合的选择,医生应帮助每位患者作出体现其价值观与偏好的决策。因此,弱推荐并非指推荐意见质量差或不采用,而是应更加谨慎或结合患者的具体情况进行决策。

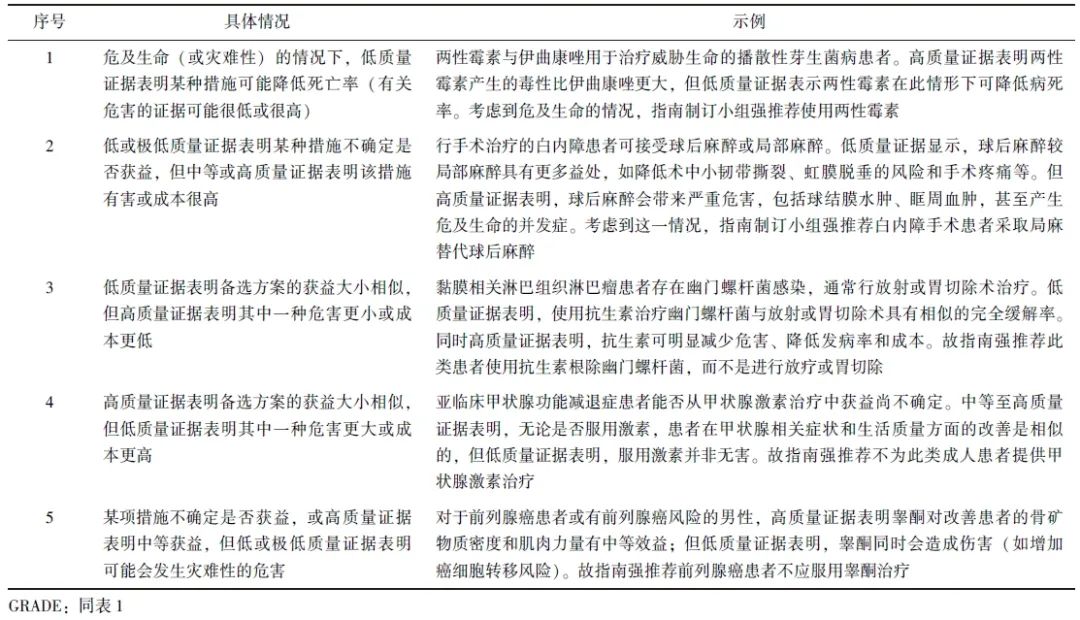

2.3 基于低或极低质量证据形成强推荐的情况

关键结局指标的证据质量越高,越有可能形成强推荐。但GRADE工作组提出,在5种特殊情况下也存在基于低(C级)或极低(D级)质量证据作出强推荐的可能性(表4)[20,56]。

表4 GRADE分级系统中基于低或极低质量证据形成强推荐的5种情况[20,56]

研究显示,基于低质量证据的强推荐在指南中并不少见,但仅少数符合GRADE工作组的要求。大部分强推荐意见不合理,未提供相关解释[57-60],也忽略了患者个体需求的复杂性[61]。

2.4 证据质量是影响推荐意见的重要因素,但不是唯一因素

除证据质量外,成本费用、价值观与偏好、可及性、公平性等其他因素也可对推荐意见产生影响,指南制订者需进行综合考虑[52,56]。以价值观与偏好为例,其通常是指患者或公众对健康的看法、认知、期望和目标。针对同一问题,当多个有效方案并存时,不同方案的风险如何,是否更加耗时、成本更高、投入精力更多,均可对最终决策产生影响,尤其是证据质量较低时。EtD方法能够系统总结不同因素对推荐意见的影响,促进整个过程更加科学透明。对于指南使用者,EtD框架有助于其理解推荐意见的产生过程,促进推荐意见的实施[49,62]。鉴于篇幅有限,本文将不对其具体内容进行阐释,感兴趣的读者可参考相关研究论文。

2.5 低质量证据或弱推荐对未来临床研究开展具有重要启示

在开展新的原始研究之前,理论上必须先针对该问题开展系统评价[63]。对于指南的使用者,推荐意见不仅是帮助其开展循证决策、规范诊疗行为的重要参考,更是发现科学问题的突破口,尤其是指南中基于低质量证据形成的弱推荐。对于指南的制订者,在形成推荐意见后,可基于对已有证据的掌握,提出研究空白或未来研究的建议,并在指南全文中汇总呈现[40,64],促进未来高质量证据的生产。

以2023年世界卫生组织发布的《6~23月龄婴幼儿辅食喂养指南》为例[65],该指南就“母乳喂养、乳制品选择、辅食的引入及选择、营养补充品、强化食品”等多个方面给出了15条推荐意见,其中3条基于极低质量证据,9条基于低质量证据,并提出了16条具体的临床研究选题。

3 小结

低质量证据在临床实践中普遍存在,但其并非无用的证据,也不决定指南的质量,甚至可以支持高级别推荐。基于低质量证据形成的推荐意见,仍然可为临床实践提供重要指导,同时也可为临床研究的开展提供优先和重要选题。正确理解和应用低质量证据,对于指南制订者、使用者和临床研究的开展者均具有重要意义和价值。

参考文献

[1]Institute of Medicine. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust[M]. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2011.

[2]Mc Allister M, Florez I D, Stoker S, et al. Advancing guideline quality through country-wide and regional quality assessment of CPGs using AGREE: a scoping review[J]. BMC Med Res Methodol, 2023, 23(1): 283.

[3]Zhou Q, Wang Z J, Shi Q L, et al. Clinical epidemiology in China series. Paper 4: the reporting and methodological quality of Chinese clinical practice guidelines published between 2014 and 2018: a systematic review[J]. J Clin Epidemiol, 2021, 140: 189-199.

[4]Guyatt G H, Oxman A D, Vist G E, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations[J]. BMJ, 2008, 336(7650): 924-926.

[5]周奇, 董冲亚, 王业明, 等. 循证医学理念在指导临床研究与实践中的作用: 基于对抗病毒药物治疗新型冠状病毒肺炎的思考[J]. 中国循证医学杂志, 2022, 22(4): 373-379.

[6]Guyatt G, Oxman A D, Akl E A, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables[J]. J Clin Epidemiol, 2011, 64(4): 383-394.

[7]Andrews J, Guyatt G, Oxman A D, et al. GRADE guidelines: 14. Going from evidence to recommendations: the significance and presentation of recommendations[J]. J Clin Epidemiol, 2013, 66(7): 719-725.

[8]Guyatt G H, Oxman A D, Vist G, et al. GRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence--study limitations (risk of bias)[J]. J Clin Epidemiol, 2011, 64(4): 407-415.

[9]Amstutz A, Speich B, Mentré F, et al. Effects of remdesivir in patients hospitalised with COVID-19: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials[J]. Lancet Respir Med, 2023, 11(5): 453-464.

[10]Beigel J H, Tomashek K M, Dodd L E, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of covid-19 - final report[J]. N Engl J Med, 2020, 383(19): 1813-1826.

[11]Wang Y M, Zhang D Y, Du G H, et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial[J]. Lancet, 2020, 395(10236): 1569-1578.

[12]Jacobson R M, Pignolo R J, Lazaridis K N. Clinical trials for special populations: children, older adults, and rare diseases[J]. Mayo Clin Proc, 2024, 99(2): 318-335.

[13]Hanlon P, Hannigan L, Rodriguez-Perez J, et al. Representation of people with comorbidity and multimorbidity in clinical trials of novel drug therapies: an individual-level participant data analysis[J]. BMC Med, 2019, 17(1): 201.

[14]陈耀龙, 杨克虎. 正确理解、 制订和使用临床实践指南[J]. 协和医学杂志, 2018, 9(4): 367-373.

[15]Liu E M, Smyth R L, Luo Z X, et al. Rapid advice guidelines for management of children with COVID-19[J]. Ann Transl Med, 2020, 8(10): 617.

[16]Lamontagne F, Fowler R A, Adhikari N K, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for supportive care of patients with Ebola virus disease[J]. Lancet, 2018, 391(10121): 700-708.

[17]Ou J Y, Li J Y, Liu Y, et al. Quality appraisal of clinical guidelines for Helicobacter pylori infection and systematic analysis of the level of evidence for recommendations[J]. PLoS One, 2024, 19(4): e0301006.

[18]Murayama A, Kamamoto S, Murata N, et al. Evaluation of financial conflicts of interest and quality of evidence in Japanese gastroenterology clinical practice guidelines[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2023, 38(4): 565-573.

[19]Weissman S, Goldowsky A, Aziz M, et al. Colorectal cancer screening guidelines are primarily based on low-moderate-quality evidence[J]. Dig Dis Sci, 2021, 66(12): 4208-4219.

[20]Chong M C, Sharp M K, Smith S M, et al. Strong recommendations from low certainty evidence: a cross-pal analysis of a suite of national guidelines[J]. BMC Med Res Methodol, 2023, 23(1): 68.

[21]Alexander P E, Bero L, Montori V M, et al. World Health Organization recommendations are often strong based on low confidence in effect estimates[J]. J Clin Epidemiol, 2014, 67(6): 629-634.

[22]Zhang Z H, Hong Y C, Liu N. Scientific evidence underlying the recommendations of critical care clinical practice guidelines: a lack of high level evidence[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2018, 44(7): 1189-1191.

[23]周奇, 王玲, 杨楠, 等. 基于GRADE康复临床实践指南证据质量与推荐强度研究[J]. 中国康复理论与实践, 2020, 26(2): 156-160.

[24]Miles K E, Rodriguez R, Gross A E, et al. Strength of recommendation and quality of evidence for recommendations in current Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines[J]. Open Forum Infect Dis, 2021, 8(2): ofab033.

[25]Mamada H, Murayama A, Kamamoto S, et al. Evaluation of financial and nonfinancial conflicts of interest and quality of evidence underlying psoriatic arthritis clinical practice guidelines: analysis of personal payments from pharmaceutical companies and authors' self-citation rate in Japan and the United States[J]. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), 2023, 75(6): 1278-1286.

[26]Fleming P S, Koletsi D, Ioannidis J P A, et al. High quality of the evidence for medical and other health-related interventions was uncommon in Cochrane systematic reviews[J]. J Clin Epidemiol, 2016, 78: 34-42.

[27]Howick J, Koletsi D, Ioannidis J P A, et al. Most healthcare interventions tested in Cochrane reviews are not effective according to high quality evidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J Clin Epidemiol, 2022, 148: 160-169.

[28]Conway A, Conway Z, Soalheira K, et al. High quality of evidence is uncommon in Cochrane systematic reviews in anaesthesia, critical care and emergency medicine[J]. Eur J Anaesthesiol, 2017, 34(12): 808-813.

[29]Xun Y Q, Guo Q Q, Ren M J, et al. Characteristics of the sources, evaluation, and grading of the certainty of evidence in systematic reviews in public health: a methodological study[J]. Front Public Health, 2023, 11: 998588.

[30]Kane R L, Butler M, Ng W. Examining the quality of evidence to support the effectiveness of interventions: an analysis of systematic reviews[J]. BMJ Open, 2016, 6(5): e011051.

[31]Shi H S, Deng P, Dong C D, et al. Quality of evidence supporting the role of tripterygium glycosides for the treatment of diabetic kidney disease: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses[J]. Drug Des Devel Ther, 2022, 16: 1647-1665.

[32]Pandis N, Fleming P S, Worthington H, et al. The quality of the evidence according to GRADE is predominantly low or very low in oral health systematic reviews[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(7): e0131644.

[33]Peng L F, Fan M X, Li J H, et al. Evidence quality assessment of sodium tanshinone IIA sulfonate injection intervention coronary heart disease angina pectoris: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses[J]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2023, 102(44): e35509.

[34]Zhang J, Yu Q Y, Peng L, et al. Benefits and safety of Chinese herbal medicine in treating psoriasis: an overview of systematic reviews[J]. Front Pharmacol, 2021, 12: 680172.

[35]Jin Y H, Wang G H, Sun Y R, et al. A critical appraisal of the methodology and quality of evidence of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of traditional Chinese medical nursing interventions: a systematic review of reviews[J]. BMJ Open, 2016, 6(11): e011514.

[36]Kong Y K, Wei X Q, Duan L, et al. Rating the quality of evidence: the GRADE system in systematic reviews/meta-analyses of AKI[J]. Ren Fail, 2015, 37(7): 1089-1093.

[37]Fu G J, Fan X M, Liang X, et al. An overview of systematic reviews of Chinese herbal medicine in the treatment of migraines[J]. Front Pharmacol, 2022, 13: 924994.

[38]Wang L, Du X Y, Hu P, et al. Quality of evidence supporting the role of acupuncture for breast cancer-related lymphoedema: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses[J]. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 2023, 149(18): 16669-16678.

[39]Brouwers M C, Kho M E, Browman G P, et al. AGREE Ⅱ: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care[J]. CMAJ, 2010, 182(18): E839-E842.

[40]Chen Y L, Yang K H, Maru ic A, et al. A reporting tool for practice guidelines in health care: the RIGHT statement[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2017, 166(2):128-132.

[41]Yang N, Liu H, Zhao W, et al. Development of the scientific, transparent and applicable rankings (STAR) tool for clinical practice guidelines[J]. Chin Med J (Engl), 2023, 136(12): 1430-1438.

[42]中华医学会杂志社指南与标准研究中心, 中国医学科学院循证评价与指南研究创新单元(2021RU017), 世界卫生组织指南实施与知识转化合作中心, 等. 2022年医学期刊发表中国指南和共识的科学性、透明性和适用性的评级[J]. 中华医学杂志, 2023, 103(37): 2912-2920.

[43]Barker T H, Dias M, Stern C, et al. Guidelines rarely used GRADE and applied methods inconsistently: a methodo-logical study of Australian guidelines[J]. J Clin Epidemiol, 2021, 130: 125-134.

[44]World Health Organization. WHO handbook for guideline development[M]. 2nd ed. Geneva: WHO Press, 2014.

[45]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Developing NICE guidelines: the manual[M/OL]. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2024(2024-01-17)[2024-04-02]. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg20/resources/developing-nice-guidelines-the-manual-pdf-72286708700869.

[46]Guidelines International Network, McMaster University. GIN-McMaster guideline development checklist[M/OL]. [2024-04-02]. https://macgrade.mcmaster.ca/resources/gin-mcmaster-guideline-development-checklist/.

[47]Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). A guideline developer's handbook[M/OL]. [2024-04-02]. https://www.sign.ac.uk.

[48]陈耀龙, 杨克虎, 王小钦, 等. 中国制订/修订临床诊疗指南的指导原则(2022版)[J]. 中华医学杂志, 2022, 102(10): 697-703.

[49]Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann H J, Moberg J, et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction[J]. BMJ, 2016, 353: i2016.

[50]Guyatt G H, Oxman A D, Kunz R, et al. GRADE guidelines: 2. Framing the question and deciding on important outcomes[J]. J Clin Epidemiol, 2011, 64(4): 395-400.

[51]Guyatt G, Oxman A D, Sultan S, et al. GRADE guidelines: 11. Making an overall rating of confidence in effect estimates for a single outcome and for all outcomes[J]. J Clin Epidemiol, 2013, 66(2): 151-157.

[52]Guyatt G H, Oxman A D, Kunz R, et al. What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians?[J]. BMJ, 2008, 336(7651): 995-998.

[53]Karanicolas P J, Davies E, Kunz R, et al. The pylorus: take it or leave it? Systematic review and meta-analysis of pylorus-preserving versus standard whipple pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary cancer[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2007, 14(6): 1825-1834.

[54]Guyatt G H, Oxman A D, Schünemann H J, et al. GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology[J]. J Clin Epidemiol, 2011, 64(4): 380-382.

[55]杨克虎, 陈耀龙, 孙凤, 等. GRADE在系统评价和实践指南中的应用[M]. 第2版. 北京: 中国协和医科大学出版社, 2021: 3.

[56]Andrews J C, Schünemann H J, Oxman A D, et al. GRADE guidelines: 15. Going from evidence to recommendation-determinants of a recommendation's direction and strength[J]. J Clin Epidemiol, 2013, 66(7): 726-735.

[57]Bautista-Orduno K G, Dorsey-Trevino E G, Gonzalez-Gonzalez J G, et al. American Thyroid Association guidelines are inconsistent with grading of recommendations assess-ment, development, and evaluations-a meta-epidemiologic study[J]. J Clin Epidemiol, 2020, 123: 180-188.e2.

[58]谢方瑜, 孙秀杰, 芦秀燕, 等. 低质量证据强推荐意见在中国护理实践指南中的现状分析[J]. 护理学报, 2021, 28(20): 39-43.

[59]Alexander P E, Brito J P, Neumann I, et al. World Health Organization strong recommendations based on low-quality evidence (study quality) are frequent and often inconsistent with GRADE guidance[J]. J Clin Epidemiol, 2016, 72: 98-106.

[60]Yao L, Ahmed M M, Guyatt G H, et al. Discordant and inappropriate discordant recommendations in consensus and evidence based guidelines: empirical analysis[J]. BMJ, 2021, 375: e066045.

[61]Yao L, Guyatt G H, Djulbegovic B. Can we trust strong recommendations based on low quality evidence?[J]. BMJ, 2021, 375: n2833.

[62]Meneses-Echavez J F, Bidonde J, Montesinos-Guevara C, et al. Using evidence to decision frameworks led to guidelines of better quality and more credible and transparent recommendations[J]. J Clin Epidemiol, 2023, 162: 38-46.

[63]Lund H, Brunnhuber K, Juhl C, et al. Towards evidence based research[J]. BMJ, 2016, 355: i5440.

[64]刘辉, 兰慧, 赵思雅, 等. 2019年期刊公开发表的中国临床实践指南文献调查与评价:研究空白[J]. 协和医学杂志, 2022, 13(3): 498-505.

[65]WHO. WHO guideline for complementary feeding of infants and young children 6-23 months of age[M]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2023.