【综述】| 原发灶不明肿瘤诊断与治疗研究进展

时间:2025-02-17 12:08:57 热度:37.1℃ 作者:网络

[摘要] 原发灶不明肿瘤(cancer of unknown primary,CUP)是一类经组织病理学确认为转移,但经系统性检查仍然无法明确原发灶的转移性肿瘤的统称,约占全球所有癌症新发病例的3%~5%,其总生存期(overall survival,OS)仅2.7~16.0个月。CUP因原发灶的隐匿性及异质性导致其诊断成为长期困扰临床医师的关键问题,也是CUP精准治疗最大的阻碍。在诊断方面,在免疫组织化学时代,两轮标志物的诊断可以让大约70%的CUP明确原发灶,然而,免疫组织化学对于原发不明未分化癌的诊断价值极其有限,且结果易受实验因素及人为因素干扰。近年来,随着肿瘤诊断进入分子检测时代,基于细胞学、组织学、基因表达谱(gene expression profiling,GEP)、基因组及表观基因组分析等技术已经能够准确地检出90%的原发灶。目前,国内可帮基因公司研发的90基因肿瘤组织起源检测已被证实诊断CUP原发灶的准确率高达94.4%,为CUP的精准治疗奠定了基础。在治疗方面,CUP既往的治疗是采用铂类药物和紫杉类药物的经验性化疗方案,患者的生存及预后并没有得到显著改善。自2008年以来,全球范围内陆续开展了分子检测指导的CUP器官特异性治疗的临床研究,但因研究设计缺陷以及结果争议等问题,尚未在国际范围内达成共识。器官特异性治疗相较于经验性化疗可改善患者的无进展生存期(progression-free survival,PFS)和OS。有鉴于此,2017年,复旦大学附属肿瘤医院多原发与不明原发肿瘤诊治中心开展了全球首个Ⅲ期临床研究,结果证实,90基因检测指导的器官特异性治疗可显著地改善患者的PFS,且OS有获益的趋势,两组患者在不良反应方面的差异无统计学意义,由此奠定了器官特异性治疗在CUP一线治疗中的地位。本文综述CUP的流行病学、发病机制、临床特征及CUP诊断从免疫组织化学时代到分子检测时代的进步,也将介绍CUP治疗从经验性化疗到分子检测指导的器官特异性治疗的进展。此外,本文详述二线治疗方案的探索以及临床分层管理模式的建立是未来CUP研究领域的两个重要方向。本综述旨在总结CUP诊断与治疗的进展,进一步明确CUP的研究方向,以最大程度地改善CUP患者的生存及预后。

[关键词] 原发灶不明肿瘤;肿瘤分子检测;经验性化疗;器官特异性治疗

[Abstract] Cancer of unknown primary (CUP) refers to a group of histopathologically confirmed malignancies that cannot be identified in terms of their primary origin despite thorough investigations. CUP accounts for approximately 3%-5% of all newly diagnosed cancers worldwide, with an overall survival (OS) ranging from 2.7 to 16.0 months. CUP has long been a significant scientific challenge due to the elusive nature and heterogeneity of the primary sites. In the era of immunohistochemistry (IHC), IHC has been applied to identify the primary site in approximately 70% of CUP cases. However, IHC also has limitations for undifferentiated cancers of unknown primary, and results can be influenced by experimental and human factors. In recent years, with the development of molecular tumor profiling (MTP), techniques such as cytology, histology, gene expression profiling (GEP), genomics and epigenomics have been able to accurately detect the primary site in 90% of cases. Currently, the 90-gene tumor tissue origin test has been proven to have an accuracy rate of 94.4% in diagnosing the primary site of CUP, laying the foundation for precision treatment. In the past, platinum and taxane-based empirical chemotherapy was commonly used for treating CUP. However, these treatments did not yield significant improvements in patient survival and prognosis. Since 2008, there has been a global emergence of clinical studies on MTP-guided first-line therapy for CUP. However, due to study design flaws and result controversies, there is no international consensus on the superiority of organ-specific treatment over empirical chemotherapy in terms of improving progression-free survival (PFS) and OS for CUP. Based on this, our center conducted the world's first phase Ⅲ clinical trial in 2017, and demonstrated improved PFS and favorable OS by GEP-guided site-specific therapy of CUP, which established the primacy of site-specific first-line therapy for CUP. In this review, we detailed the epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical characteristics and the progression of CUP diagnosis from the era of IHC to MTP. Furthermore, we reviewed the advancements in CUP treatment from empirical chemotherapy to MTP-guided organ-specific treatment. Additionally, this review delved into the exploration of second-line treatment options and the establishment of a clinical stratified management model, which are two topics in future research of CUP. This review aimed to summarize the progress in the diagnosis and treatment of CUP, further explore future research directions for CUP, and improve the survival and prognosis of patients with CUP.

[Keywords] Cancer of unknown primary; Molecular tumor profiling; Empirical chemotherapy; Site-specific therapy

原发灶不明肿瘤(cancer of unknown primary,CUP)是一类经组织病理学确认为转移,但经系统检查仍找不到原发灶的转移性肿瘤的统称,占所有恶性肿瘤的3%~5%[1]。CUP是全球第四位常见肿瘤致死病因[2],患者预后较差,总生存期(overall survival,OS)仅2.7~16.0个月[3],主要是因为CUP原发灶诊断不明为临床治疗决策带来阻碍。因此,精准的原发灶诊断和治疗策略的优化,是改善CUP患者生存及预后的关键环节。

CUP原发灶诊断困难的主要原因包括:检查不全面、病理学采样不足、原发灶隐匿、原发灶缺失、原发灶自发消退以及肿瘤广泛转移导致原发灶难以辨别等。过去50年,CUP的诊断经历了从免疫组织化学时代向肿瘤分子检测(molecular tumor profiling,MTP)时代的进步。目前公认的“免疫组织化学染色两步法”已被广泛应用于CUP的临床诊断[4]。然而,免疫组织化学染色仍然存在一定的局限性,仅依靠免疫组织化学染色诊断CUP的准确率约为77%[5],尤其是对低分化和未分化的CUP,免疫组织化学染色的诊断价值有限。近10年,随着MTP技术在肿瘤诊断领域的广泛应用,基因表达谱检测(gene expression profiling,GEP)、基因组学及表观遗传学分析被广泛应用于CUP原发灶检测,其诊断的准确率高达83%~94%[6-7]。近年来,原发灶不明肿瘤(cancer of unknown primary,CUP)是一类经组织病理学确认为转移,但经系统检查仍找不到原发灶的转移性肿瘤的统称,占所有恶性肿瘤的3%~5%[1]。CUP是全球第四位常见肿瘤致死病因[2],患者预后较差,总生存期(overall survival,OS)仅2.7~16.0个月[3],主要是因为CUP原发灶诊断不明为临床治疗决策带来阻碍。因此,精准的原发灶诊断和治疗策略的优化,是改善CUP患者生存及预后的关键环节。

CUP原发灶诊断困难的主要原因包括:检查不全面、病理学采样不足、原发灶隐匿、原发灶缺失、原发灶自发消退以及肿瘤广泛转移导致原发灶难以辨别等。过去50年,CUP的诊断经历了从免疫组织化学时代向肿瘤分子检测(molecular tumor profiling,MTP)时代的进步。目前公认的“免疫组织化学染色两步法”已被广泛应用于CUP的临床诊断[4]。然而,免疫组织化学染色仍然存在一定的局限性,仅依靠免疫组织化学染色诊断CUP的准确率约为77%[5],尤其是对低分化和未分化的CUP,免疫组织化学染色的诊断价值有限。近10年,随着MTP技术在肿瘤诊断领域的广泛应用,基因表达谱检测(gene expression profiling,GEP)、基因组学及表观遗传学分析被广泛应用于CUP原发灶检测,其诊断的准确率高达83%~94%[6-7]。近年来,随着人工智能(artificial intelligence,AI)在肿瘤诊疗中的应用,基于细胞学、组织病理学、GEP、基因组学及表观基因组学的深度学习或机器学习模型在预测CUP的原发灶方面表现出了卓越的性能[1,8-11],为CUP原发灶的诊断开辟了新的思路。

在过去的20年中,以紫杉类药物和铂类药物为基础的经验性联合化疗是CUP治疗的基石。然而,大量的临床研究证实,经验性化疗并没有显著延长CUP患者的OS和无进展生存期(progression-free survival,PFS)。为了探究器官特异性治疗相较于经验性化疗是否可以改善患者的生存和预后,国内外陆续开展了一系列基于MTP指导的器官特异性治疗的临床试验[12-16]。2013年,美国萨拉·坎农研究所开展的一项Ⅱ期临床研究证实,GEP指导的器官特异性治疗相较于经验性化疗可以改善CUP患者的OS[12]。2019年,日本近畿大学开展的另一项Ⅱ期临床研究[13]显示,器官特异性治疗相较于经验性化疗并不能延长患者的OS和PFS。然而,以上研究均存在一定的局限性,包括样本量不足、诊断模型的效能有待提升等,且结论存在争议。有鉴于此,2017年,复旦大学附属肿瘤医院多原发和不明原发肿瘤诊治中心开展了全球首个90基因表达谱检测指导的器官特异性治疗的前瞻性随机对照Ⅲ期临床研究[16],结果表明,器官特异性治疗可以改善CUP患者的PFS,而OS差异无统计学意义。

该研究奠定了器官特异性治疗在CUP一线治疗中的地位,开启了CUP治疗的新时代。展望未来,我们相信诊断技术的优化以及二线或后线治疗方案的探索将是未来CUP研究领域的两个重要方向。本文详述CUP的流行病学、发病机制以及临床特征,并介绍CUP诊断和治疗研究的进展。

1 CUP的流行病学

CUP占全球所有恶性肿瘤的3%~5%,然而,在不同的国家和地区因其定义及医疗水平的差异而略有不同[17]。在苏格兰,1961—2010年CUP患者的年龄标准化发病率(age-standardized incidence rate,ASIR)为每10万人口5~18例,1990年代中期达峰值后急剧下降,占所有确诊恶性肿瘤的3.9%[18]。在瑞典,1960—2008年CUP患者的ASIR约为每10万人口4~8例,于1990年代末期达峰值后显著下降,占所有确诊恶性肿瘤的3.9%[19]。在瑞士,1981—1997年CUP患者的ASIR从每10万人口10.3上升至17.6,然后在2014年下降至5.8,占所有确诊恶性肿瘤的0.9%~2.6%[20]。从欧洲的流行病学数据来看,大部分国家和地区CUP患者的ASIR在1990年代达到峰值后开始显著下降,主要是因为诊断方法的进步提高了原发灶的检出率。相较于欧洲,美国CUP的ASIR从20世纪80年代早期就呈现出下降趋势。2000—2010年,美国CUP患者的平均ASIR为每10万人口4.1例[21]。然而,到目前为止,亚洲人群的CUP发病率尚未有详细的流行病学数据统计。复旦大学附属肿瘤医院多原发和不明原发肿瘤诊治中心2019—2020年的统计数据显示,CUP约占所有癌症确诊病例的0.82%[22]。事实上,各国家和地区CUP发病率的下降主要是由于诊断技术的进步显著提高了原发灶的检出率[23],使CUP确诊病例的数量呈现出逐渐减少的趋势。

2 CUP的发病机制

原发灶的隐匿性和转移灶的异质性导致CUP发病机制方向的研究仍是空白,目前公认的主要是两个学说:“无原发灶理论”认为失控的、癌前状态的干细胞或肿瘤干细胞迁移到新的部位,在转移部位形成肿瘤[24],或者原发灶在形成可检测病变之前已经消失[25-26],这种情况下不存在原发灶,因而称为 “无原发灶理论”;“平行进展理论”则认为原发病灶的肿瘤细胞早期迁移到新的部位,进而重塑肿瘤微环境,促进转移灶的定植和生长[26],抑制原发灶的生长和进展[28],从而导致原发灶难以检出。这种情况下,4%~25%的患者随着疾病的进展会逐渐暴露原发灶[27]。

3 CUP的临床特征

CUP患者通常因转移灶的症状和体征而就诊,包括浅表淋巴结肿大、局部肿块、骨痛、腹胀等。其中,淋巴结肿大是最常见的就诊原因,占所有就诊病例的14.0%~41.8%[22,28-29],因此,肿大淋巴结的部位可作为CUP溯源的重要依据。总体来看,CUP原发常见于肝脏[14]、 肺[29]、胰腺[30]、乳腺[7]和肠道[3]。

组织学特征方面,CUP可以分为4种组织学类型,包括高度和中度分化的腺癌(50%)、差分化腺癌或未分化癌(30%)、鳞状细胞癌(15%)和未分化肿瘤(5%)。肉瘤、黑色素瘤、神经内分泌肿瘤、生殖细胞肿瘤和血液系统恶性肿瘤不纳入CUP定义的范畴。组织学分类是经验性化疗的基础,不同的组织学类型治疗反应不同。鳞状细胞癌患者的生存率较腺癌及未分化癌患者高,其1年生存率分别为46%和19%[31],主要是因为不同组织学类型的CUP之间存在不同的基因表达和激活不同的致癌信号转导通路。

遗传学特征方面,TP53、KRAS、CDKN2A、MET、MYC和ARID1A是CUP最常见的基因突变[32-34],而CDKN2A是最常见的缺失基因[35]。同时,ERBB2、EGFR和BRAF基因突变在原发不明腺癌中更为常见,而MLL2基因突变则在原发不明非腺癌中更常见[32],且原发不明腺癌的RAS/丝裂原活化蛋白激酶(mitogen-activated protein kinases,MAPK)信号转导通路激活较非腺癌更强[32],主要与腺癌具有更高的FGFR2、KRAS和ALK表达相关。此外,FGFR2是最常见的融合基因伴侣,其次是ALK[35]。FGFR2的完整激酶结构域与另一基因融合后提供一个二聚化结构域,激活下游的RAS/MAPK和磷脂酰肌醇3-激酶(phosphoinositide3-kinase,PI3K)/蛋白激酶B(protein kinase,AKT)信号转导通路。研究[36]证实,约14%的CUP高表达程序性死亡受体配体1(programmed death-ligand 1,PD-L1)(>50%),且不同组织学类型PD-L1的表达差异无统计学意义;同时,约16%的CUP显示出高肿瘤突变负荷(tumor mutation burden,TMB)(>10个突变/Mb),这为CUP患者应用免疫检查点抑制剂治疗(immune checkpoint inhibitor,ICI)提供了理论依据。另外,有研究[38-39]证实CUP患者HER2阳性的比例约为10%,为靶向HER2的抗体药物偶联物(antibody-drug conjugate,ADC)治疗CUP提供了可能。

4 CUP的诊断

4.1 临床常规检查

临床常规检查内容包括病史采集、体格检查及血液学等检查。病史采集包括对症状和体征、既往检查、既往病史、治疗经过、手术史以及肿瘤家族史的全面评估。专科体检应包括对局部肿块、浅表淋巴结、泌尿生殖道、乳房和直肠的体检。在CUP患者中,淋巴结肿大是最常见且最重要的阳性体征,为追踪CUP的原发灶提供了宝贵线索。例如,颈部淋巴结肿大通常提示头颈部鳞癌转移以及来自唾液腺、甲状腺、肺、乳腺、胃肠和泌尿生殖道肿瘤的转移[40]。复旦大学附属肿瘤医院多原发和不明原发肿瘤诊治中心发表在BMC Cancer的研究证实,“前哨淋巴结理论”可为95%的淋巴结转移的CUP患者预测原发灶[41]。此外,血常规、肿瘤标志物等检测也属于CUP诊断的常规检查范畴。肿瘤标志物已广泛应用于临床肿瘤筛查、诊断、复发监测和疗效评估。某些特定的肿瘤标志物对肿瘤患者的生存及预后具有预测价值,如血清乳酸脱氢酶(lactate dehydrogenase,LDH)水平升高已被证明与多种类型的肿瘤患者的预后密切相关[42]。然而,肿瘤标志物的敏感性和特异性有限,其主要用于其他检查的辅助检查帮助CUP诊断,或用于患者临床初筛、复发监测及疗效评估。

4.2 影像及核医学检查

计算机断层扫描(computed tomography,CT)和磁共振成像(magnetic resonance imaging,MRI)已被广泛应用于肿瘤的临床诊断、疗效评估及随访。近年来,随着分子影像学在肿瘤诊断领域的发展,正电子发射断层扫描(positron emission tomography,PET)与CT或MRI的结合已被广泛应用于肿瘤临床诊断和疗效评估。18F-脱氧葡萄糖(fluorodeoxyglucose,FDG)PET/CT目前已应用于CUP患者的诊断、治疗监测和预后评估[43-46]。总体而言,对于以淋巴结肿大为首发症状的CUP,18F-FDG PET/CT预测CUP原发灶的灵敏度、特异度和准确率分别为73%、89%和81%[43]。其中,尤其对于以颈部淋巴结肿大为首发症状的CUP,18F-FDG PET/CT表现出更优的性能,灵敏度、特异度和准确率分别为88.3%、74.9%和78.8%[45]。此外,该研究还证实18F-FDG PET/CT能够在25%的CUP病例中检测到其他检查方法未能发现的病灶,以及在27%的CUP病例中揭示以前未被发现的局部或远处转移病灶。同时,18F-FDG PET/CT SUVmax大于20被证明与CUP患者预后良好相关[44],可能是因为SUVmax在明确瘤种化疗敏感性方面的预测价值。此外,复旦大学附属肿瘤医院核医学科发表的研究证实68Ga-FAPI PET/CT可以提高头颈部淋巴结转移的CUP患者的原发灶检出率,尤其是对于18F-FDG PET/CT检查阴性的CUP患者[47],因此,68Ga-FAPI PET/CT有望为头颈部淋巴结转移的CUP提供更高效的诊断。

4.3 免疫组织化学染色

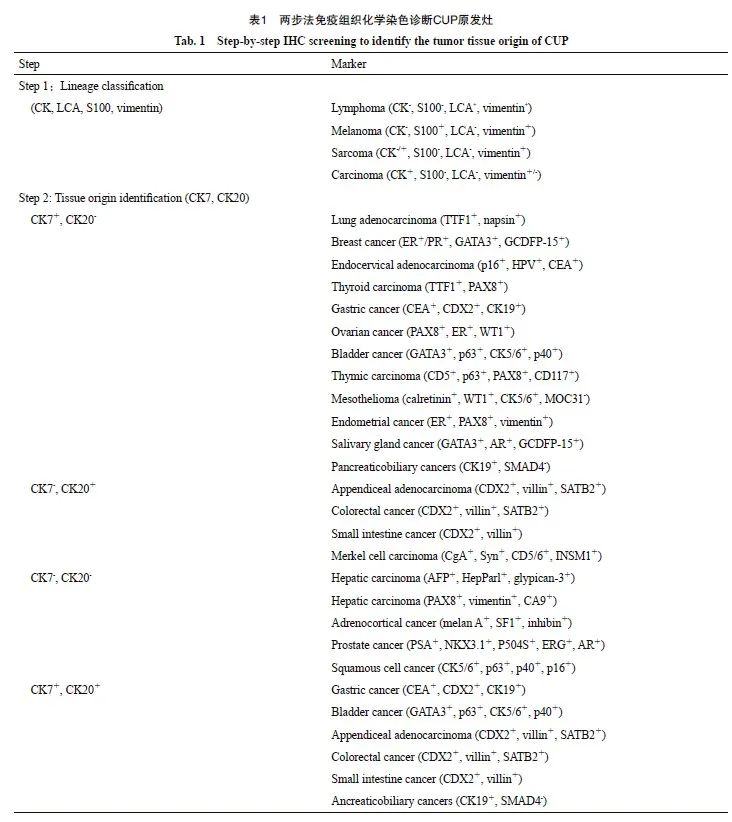

组织病理学是诊断CUP的“金标准”,包括形态学分析和免疫组织化学染色[48]。肿瘤细胞的形态往往可以为原发灶的判断提供蛛丝马迹,如黏液腺癌细胞常见于胃肠道的腺上皮,而乳头状肿瘤细胞主要见于乳腺和甲状腺癌。然而,对于未分化和差分化的CUP,仅依靠形态学分析是远远不够的,此时免疫组织化学染色就显得尤为重要。目前公认应用“免疫组织化学染色两步法” 策略推测CUP的原发灶:第一步,应用谱系特异性的标志物(CK、S100、LCA和vimentin)将癌和淋巴瘤、肉瘤及黑色素瘤进行区分;第二步,当明确为上皮来源的恶性肿瘤后,应用CK7和CK20推测可能的组织来源(表1)。免疫组织化学染色在非小细胞肺癌、乳腺癌、结直肠癌、卵巢癌和肾癌等原发的CUP诊断中表现出较高的灵敏度和准确率,然而,当原发灶来源于胃癌、胰腺癌或胆管癌时,其特异性较低。总体而言,免疫组织化学染色诊断CUP的准确率约为77%[5]。尤其对于差分化和未分化癌,免疫组织化学染色对于CUP原发灶的诊断价值更加有限。此外,组织抗原的不稳定性、肿瘤的异质性和不同病理科医师对免疫组织化学染色结果的主观判断存在差异等因素,是导致免疫组织化学染色诊断CUP准确率降低的常见原因。因此,CUP诊断技术的优化仍然是该领域最重要的研究方向。

4.4 肿瘤分子检测

近20年来,随着MTP技术在肿瘤诊断中的广泛应用,其逐渐被应用于诊断CUP的原发灶[35,49],主要包括GEP、基因组和表观基因组分析。MTP相较于免疫组织化学染色需要的组织量更少,且诊断的准确率更高。研究[29]证实, MTP诊断CUP原发灶的准确率最高可达94.4%,为基于MTP的器官特异性治疗奠定了基础。

GEP主要包括基于芯片或PCR两种平台检测技术,检测基因的数量从10到2 000个不等。研究[51]证实,10个基因诊断CUP的准确率为60.6%[50],而CupPrintTM芯片包含495个肿瘤组织特异性基因,诊断CUP原发灶的准确率高达92.3%。然而,仅增加检测基因的数量并不能显著提高诊断的准确率,美国食品药品监督管理局(Food and Drug Administration,FDA)批准的ToO试剂盒包含了2 000个组织特异性基因,其诊断CUP原发灶的准确率仅76.2%[52-53]。此外,包含92个基因的CancerTYPE ID试剂盒诊断CUP原发灶的准确率超过80%[54]。因此,如何通过更少的基因检测达到更准确的诊断仍然是CUP诊断方向最核心的问题。中国国家药品监督管理局批准的首个中国自主研发的90基因肿瘤组织起源检测试剂盒被证实预测CUP原发灶的准确率高达94.4%[29]。此外,microRNA因具有高度的组织特异性也被应用于CUP原发灶的诊断。研究[55-58]证实包含47~89个microRNA的检测在诊断CUP的准确率为75.0%~95.0%。

基于芯片和NGS的基因组和表观基因组分析也被尝试应用于CUP原发灶的诊断[14,35]。基因组分析可以揭示肿瘤组织的基因突变、基因重排及肿瘤突变负荷,从而为原发灶的诊断提供重要线索,同时指导靶向治疗和免疫治疗。除了基因组分析以外,表观基因组分析,如DNA甲基化检测也被证实在诊断CUP的原发灶方面具有较高的价值[59]。最近的一项研究[11]表明,DNA甲基化测序可准确地检测出81%~93%的CUP患者的原发灶。此外,对于肿瘤组织取样困难的CUP患者,循环肿瘤细胞DNA甲基化测序同样具有重要的参考价值[60]。

随着基于深度学习和机器学习的人工智能技术在肿瘤诊断、治疗预测、复发监测及预后评估中的应用,基于细胞学[10]、组织学[8]、GEP[61-62]及基因组[1,9]和表观基因组[11,63]分析的人工智能预测模型展示出了优异的效能。然而,基于单模态或者多模态的人工智能预测模型是否能够转化到临床应用,仍有待后续的深入研究。

5 CUP的治疗

CUP患者就诊时均为晚期阶段,因此局部治疗只适合少数病灶较小且局限的患者。国际公认根据CUP患者的临床特征分为预后良好(20%)和预后不良(80%)两组,预后良好组CUP患者的中位OS为12个月,而预后不良组患者的中位OS仅有4个月[64]。预后良好的CUP患者可给予局部治疗或者基于铂类药物的系统性化疗,其OS与相关系统的原发肿瘤患者预后差异无统计学意义;预后不良组主要采用基于铂类药物和紫杉类药物的经验性化疗。然而,经验性化疗并没有显著改善患者预后,且近年来许多肿瘤一线治疗方案日新月异。因此,器官特异性治疗是否能较经验性化疗显著改善患者生存和预后,仍是目前值得研究的问题。

5.1 经验性化疗

1980年以来,关于CUP经验性化疗方案的探索经历了30年的发展。鉴于CUP主要以腺癌为主,因此早期的临床研究主要聚焦于探索腺癌的化疗方案对CUP治疗的有效性,例如乳腺癌的经典CMF方案(cyclophosphamide+methotrexate+5-fluorouracil)[65]及肠癌的XELOX方案(oxaliplatin+capecitabine)和mFOLFOX6方案(oxaliplatin+leucovorin+5-fluorouracil)均被尝试应用于CUP的治疗[66-68]。2000年,一项发表在Journal of Clinical Oncology杂志的Ⅱ期临床研究[69]结果显示,紫杉醇联合卡铂一线治疗CUP的ORR为38.7%,中位OS为13个月。因此,自2000年以后,紫杉类药物联合铂类药物的治疗方案被认为是CUP经验性化疗的基石,且卡铂和顺铂在疗效及不良反应上的差异无统计学意义[70-73]。

5.2 特异性治疗

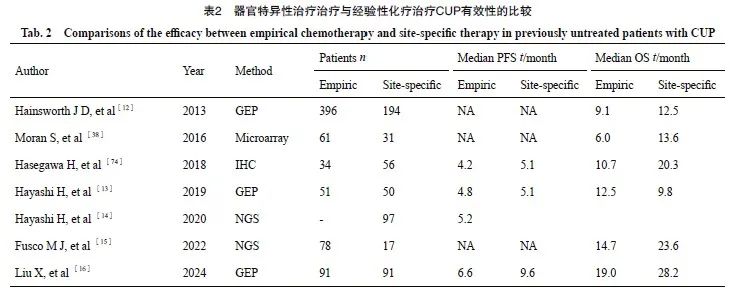

近10年来,肿瘤的治疗经历了化疗时代向免疫治疗及靶向治疗时代的发展,且肺癌、肝癌等大瘤种的一线治疗方案也开始转向免疫治疗。因此,全球范围内开展了一系列临床研究探索器官特异性治疗是否能够改善CUP患者生存和预后(表2)。2013年,美国萨拉·坎农研究所开展的一项Ⅱ期临床研究[12]证实,92基因指导的器官特异性治疗的CUP患者中位OS为12.5个月,显著优于经验性化疗患者的9.1个月。然而,这项研究的经验性化疗患者来自该中心以往的回顾性数据,可能会导致结果产生一定的偏倚,因此结果的可信度有限。2019年,日本近畿大学开展的另一项Ⅱ期临床研究[13]显示,器官特异性治疗相较于经验性化疗并没有改善CUP患者的OS(9.8个月 vs 12.5个月,P=0.896)和PFS(5.1个月 vs 4.8个月,P=0.550)。然而,这项研究仅纳入101例样本,且预测模型的诊断准确率仅为78.6%,因此结果存在一定的局限性。2022年,美国莫菲特癌症中心开展的一项临床研究证实,接受NGS指导的器官特异性治疗的CUP患者相较于经验性化疗的患者表现出更好的OS和PFS,尽管差异无统计学意义[15]。此外,2016年发表在Lancet Oncology的一项多中心回顾性研究[38]结果表明,DNA甲基化特征(EPICUP)指导的器官特异性治疗较经验性化疗能显著改善CUP患者的OS(13.6个月 vs 6.0个月,P=0.005 1)。鉴于以上研究设计的局限性和研究结论的争议,目前关于器官特异性治疗是否改善CUP患者的预后仍有待进一步研究。

有鉴于此,复旦大学附属肿瘤医院多原发和不明原发肿瘤诊治中心团队开展了全球首个对比器官特异性治疗与经验性化疗一线治疗CUP的安全性和有效性的Ⅲ期临床试验(CUP-001),研究[16]结果表明,器官特异性一线治疗可显著延长CUP患者的PFS(9.6个月 vs 6.6个月,P=0.017),而OS则差异无统计学意义(28.2个月 vs 19.0个月,P=0.099)。CUP-001研究奠定了器官特异性一线治疗在CUP临床治疗中的地位,改善了患者的预后,谱写了CUP治疗的新篇章。

6 展望

CUP的诊断与治疗历经50年的发展,逐渐进入精准治疗的时代。虽然基于GEP、基因组及表观基因组分析的诊断技术显著提高了CUP原发灶的检出率和诊断准确率,但目前关于CUP的诊断和后线治疗仍未达成共识。因此,我们认为CUP未来的研究方向仍应聚焦于诊断方式的优化和治疗方案的探索。

未来,关于CUP诊断技术将进一步优化。基于细胞学、病理学、GEP及基因组和表观基因组分析的诊断方法诊断CUP原发灶的准确率已被证实超过90%。其中,GEP检测技术应用最为广泛,可帮基因公司研发的90基因肿瘤组织起源检测已被证实诊断CUP原发灶的准确率高达94.4%[29]。未来是否能够实现更少的基因组合达到更高的诊断效率,或者借助于人工智能模型来提高原发灶的诊断准确率,仍然任重道远。

目前全球开展的临床研究主要聚焦于一线治疗方案的设计,虽然CUP001研究证实一线器官特异性治疗可改善CUP患者的PFS,但是CUP患者目前的中位PFS仍然不超过1年。CUP患者一线治疗进展后二线方案的选择相关的研究目前在全球仍处于空白阶段。2022年发表在Annual Oncology的一项Ⅱ期临床研究结果表明,纳武利尤单抗二线治疗CUP的ORR为22%,中位PFS和中位OS分别为4.0及15.9个月[75],为免疫联合治疗在CUP二线治疗中的效果探究奠定了基础。为此,复旦大学附属肿瘤医院多原发和不明原发肿瘤诊治中心开展了一项免疫治疗联合抗血管靶向治疗及化疗二线治疗CUP的有效性及安全性的Ⅱ 期临床试验,研究结果即将公布,或为CUP二线治疗提供有力的证据。

[参考文献]

[1] MOON I, LOPICCOLO J, BACA S C, et al. Machine learning for genetics-based classification and treatment response prediction in cancer of unknown primary[J]. Nat Med, 2023, 29(8): 2057-2067.

[2] LEE M S, SANOFF H K. Cancer of unknown primary[J]. BMJ, 2020, 371: m4050.

[3] RASSY E, PAVLIDIS N. Progress in refining the clinical management of cancer of unknown primary in the molecularera

[J]. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2020, 17(9): 541-554.

[4] DUM D, MENZ A, VÖLKEL C, et al. Cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20 expression in cancer: a tissue microarray study on 15 424 cancers[J]. Exp Mol Pathol, 2022, 126: 104762.

[5] GRECO F A, LENNINGTON W J, SPIGEL D R, et al. Molecular profiling diagnosis in unknown primary cancer: accuracy and ability to complement standard pathology[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2013, 105(11): 782-790.

[6] HANDORF C R, KULKARNI A, GRENERT J P, et al. A multicenter study directly comparing the diagnostic accuracy of gene expression profiling and immunohistochemistry for primary site identification in metastatic tumors[J]. Am J Surg Pathol, 2013, 37(7): 1067-1075.

[7] YE Q, WANG Q F, QI P, et al. Development and clinical validation of a 90-gene expression assay for identifying tumor tissue origin[J]. J Mol Diagn, 2020, 22(9): 1139-1150.

[8] LU M Y, CHEN T Y, WILLIAMSON D F K, et al. AI-based pathology predicts origins for cancers of unknown primary[J]. Nature, 2021, 594(7861): 106-110.

[9] NGUYEN L, VAN HOECK A, CUPPEN E. Machine learningbased tissue of origin classification for cancer of unknown primary diagnostics using genome-wide mutation features[J]. Nat Commun, 2022, 13(1): 4013.

[10] TIAN F, LIU D, WEI N, et al. Prediction of tumor origin in cancers of unknown primary origin with cytology-based deep learning[J]. Nat Med, 2024, 30(5): 1309-1319.

[11] ZHANG S R, HE S T, ZHU X, et al. DNA methylation profiling to determine the primary sites of metastatic cancers using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues[J]. Nat Commun, 2023, 14(1): 5686.

[12] HAINSWORTH J D, RUBIN M S, SPIGEL D R, et al. Molecular gene expression profiling to predict the tissue of origin and direct site-specific therapy in patients with carcinoma of unknown primary site: a prospective trial of the Sarah Cannon Research Institute[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2013, 31(2): 217-223.

[13] HAYASHI H, KURATA T, TAKIGUCHI Y, et al. Randomized phase Ⅱ trial comparing site-specific treatment based on gene expression profiling with carboplatin and paclitaxel for patients with cancer of unknown primary site[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2019, 37(7): 570-579.

[14] HAYASHI H, TAKIGUCHI Y, MINAMI H, et al. Site-specific and targeted therapy based on molecular profiling by nextgeneration sequencing for cancer of unknown primary site: a nonrandomized phase 2 clinical trial[J]. JAMA Oncol, 2020, 6(12): 1931-1938.

[15] FUSCO M J, KNEPPER T C, BALLIU J, et al. Evaluation of targeted next-generation sequencing for the management of patients diagnosed with a cancer of unknown primary[J]. Oncologist, 2022, 27(1): e9-e17.

[16] LIU X, ZHANG X W, JIANG S Y, et al. Site-specific therapy guided by a 90-gene expression assay versus empirical chemotherapy in patients with cancer of unknown primary (Fudan CUP-001): a randomised controlled trial[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2024, 25(8): 1092-1102.

[17] URBAN D, RAO A, BRESSEL M, et al. Cancer of unknown primary: a population-based analysis of temporal change and socioeconomic disparities[J]. Br J Cancer, 2013, 109(5): 1318-1324.

[18] BREWSTER D H, LANG J, BHATTI L A, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of cancer of unknown primary site in Scotland, 1961-2010[J]. Cancer Epidemiol, 2014, 38(3): 227-234.

[19] RANDÉN M, RUTQVIST L E, JOHANSSON H. Cancer patients without a known primary: incidence and survival trends in Sweden 1960-2007[J]. Acta Oncol, 2009, 48(6): 915-920.

[20] BINDER C, MATTHES K L, KOROL D, et al. Cancer of unknown primary-epidemiological trends and relevance of comprehensive genomic profiling[J]. Cancer Med, 2018, 7(9): 4814-4824.

[21] MNATSAKANYAN E, TUNG W C, CAINE B, et al. Cancer of unknown primary: time trends in incidence, United States[J]. Cancer Causes Control, 2014, 25(6): 747-757.

[22] QI P, SUN Y F, LIU X, et al. Clinicopathological, molecular and prognostic characteristics of cancer of unknown primary in China: an analysis of 1 420 cases[J]. Cancer Med, 2023, 12(2): 1177-1188.

[23] RASSY E, PAVLIDIS N. The currently declining incidence of cancer of unknown primary[J]. Cancer Epidemiol, 2019, 61: 139-141.

[24] LÓPEZ-LÁZARO M. The migration ability of stem cells can explain the existence of cancer of unknown primary site. Rethinking metastasis[J]. Oncoscience, 2015, 2(5): 467-475.

[25] OLIVIER T, FERNANDEZ E, LABIDI-GALY I, et al. Redefining cancer of unknown primary: is precision medicine really shifting the paradigm? [J]. Cancer Treat Rev, 2021, 97: 102204.

[26] RASSY E, ASSI T, PAVLIDIS N. Exploring the biological hallmarks of cancer of unknown primary: where do we stand today? [J]. Br J Cancer, 2020, 122(8): 1124-1132.

[27] JOOSSE S A, PANTEL K. Genetic traits for hematogeneous tumor cell dissemination in cancer patients[J]. Cancer Metastasis Rev, 2016, 35(1): 41-48.

[28] KOLLING S, VENTRE F, GEUNA E, et al. “Metastatic cancer of unknown primary” or “primary metastatic cancer”? [J]. Front Oncol, 2019, 9: 1546.

[29] SUN W, WU W, WANG Q F, et al. Clinical validation of a 90- gene expression test for tumor tissue of origin diagnosis: a largescale multicenter study of 1 417 patients[J]. J Transl Med, 2022, 20(1): 114.

[30] LAPROVITERA N, RIEFOLO M, AMBROSINI E, et al. Cancer of unknown primary: challenges and progress in clinical management[J]. Cancers, 2021, 13(3): 451.

[31] HEMMINKI K, BEVIER M, HEMMINKI A, et al. Survival in cancer of unknown primary site: population-based analysis by site and histology[J]. Ann Oncol, 2012, 23(7): 1854-1863.

[32] ROSS J S, WANG K, GAY L, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of carcinoma of unknown primary site: new routes to targeted therapies[J]. JAMA Oncol, 2015, 1(1): 40-49.

[33] ROSS J S, SOKOL E S, MOCH H, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of carcinoma of unknown primary origin: retrospective molecular classification considering the CUPISCO study design[J]. Oncologist, 2021, 26(3): e394-e402.

[34] VARGHESE A M, ARORA A, CAPANU M, et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of patients with cancer of unknown primary in the modern era[J]. Ann Oncol, 2017, 28(12): 3015-3021.

[35] MÖHRMANN L, WERNER M, OLEŚ M, et al. Comprehensive genomic and epigenomic analysis in cancer of unknown primary guides molecularly-informed therapies despite heterogeneity[J]. Nat Commun, 2022, 13(1): 4485.

[36] KIM H M, KOO J S. Programmed death-ligand 1 expression in carcinoma of unknown primary[J]. BMC Cancer, 2024, 24(1): 689.

[37] POSNER A, SIVAKUMARAN T, PATTISON A, et al. Immune and genomic biomarkers of immunotherapy response in cancer of unknown primary[J]. J Immunother Cancer, 2023, 11(1): e005809.

[38] MORAN S, MARTÍNEZ-CARDÚS A, SAYOLS S, et al. Epigenetic profiling to classify cancer of unknown primary: a multicentre, retrospective analysis[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2016, 17(10): 1386-1395.

[39] BRIASOULIS E, TSOKOS M, FOUNTZILAS G, et al. Bcl2 and p53 protein expression in metastatic carcinoma of unknown primary origin: biological and clinical implications. A Hellenic Co-operative Oncology Group study[J]. Anticancer Res, 1998, 18(3B): 1907-1914.

[40] GALLOWAY T J, RIDGE J A. Management of squamous cancer metastatic to cervical nodes with an unknown primary site[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2015, 33(29): 3328-3337.

[41] SHAO Y L, LIU X, HU S L, et al. Sentinel node theory helps tracking of primary lesions of cancers of unknown primary[J]. BMC Cancer, 2020, 20(1): 639.

[42] CLAPS G, FAOUZI S, QUIDVILLE V, et al. The multiple roles of LDH in cancer[J]. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2022, 19(12): 749-762.

[43] NIKOLOVA P N, HADZHIYSKA V H, MLADENOV K B, et al. The impact of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the clinical management of patients with lymph node metastasis of unknown primary origin[J]. Neoplasma, 2021, 68(1): 180-189.

[44] ZAUN G, WEBER M, METZENMACHER M, et al. SUVmax above 20 in 18F-FDG PET/CT at initial diagnostic workup associates with favorable survival in patients with cancer of unknown primary[J]. J Nucl Med, 2023, 64(8): 1191-1194.

[45] RUSTHOVEN K E, KOSHY M, PAULINO A C. The role of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in cervical lymph node metastases from an unknown primary tumor[J]. Cancer, 2004, 101(11): 2641-2649.

[46] EILSBERGER F, NOLTENIUS F E, LIBRIZZI D, et al. Reallife performance of F-18-FDG PET/CT in patients with cervical lymph node metastasis of unknown primary tumor[J]. Biomedicines, 2022, 10(9): 2095.

[47] GU B X, XU X P, ZHANG J, et al. The added value of 68Ga-FAPI PET/CT in patients with head and neck cancer of unknown primary with 18F-FDG-negative findings[J]. J Nucl Med, 2022, 63(6): 875-881.

[48] ROSSI G, NANNINI N, COSTANTINI M. Morphology and more specific immunohistochemical stains are fundamental prerequisites in detection of unknown primary cancer[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2009, 27(4): 649-650.

[49] DERMAWAN J K, RUBIN B P. The role of molecular profiling in the diagnosis and management of metastatic undifferentiated cancer of unknown primary molecular profiling of metastatic cancer of unknown primary[J]. Semin Diagn Pathol, 2021, 38(6): 193-198.

[50] VARADHACHARY G R, TALANTOV D, RABER M N, et al. Molecular profiling of carcinoma of unknown primary and correlation with clinical evaluation[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2008, 26(27): 4442-4448.

[51] VAN LAAR R K, MA X J, DE JONG D, et al. Implementation of a novel microarray-based diagnostic test for cancer of unknown primary[J]. Int J Cancer, 2009, 125(6): 1390-1397.

[52] PILLAI R, DEETER R, RIGL C T, et al. Validation and reproducibility of a microarray-based gene expression test for tumor identification in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens[J]. J Mol Diagn, 2011, 13(1): 48-56.

[53] MONZON F A, MEDEIROS F, LYONS-WEILER M, et al. Identification of tissue of origin in carcinoma of unknown primary with a microarray-based gene expression test[J]. Diagn Pathol, 2010, 5: 3.

[54] HAINSWORTH J D, SCHNABEL C A, ERLANDER M G, et al. A retrospective study of treatment outcomes in patients with carcinoma of unknown primary site and a colorectal cancer molecular profile[J]. Clin Colorectal Cancer, 2012, 11(2): 112-118.

[55] FERRACIN M, PEDRIALI M, VERONESE A, et al. MicroRNA profiling for the identification of cancers with unknown primary tissue-of-origin[J]. J Pathol, 2011, 225(1): 43-53.

[56] VARADHACHARY G R, SPECTOR Y, ABBRUZZESE J L, et al. Prospective gene signature study using microRNA to identify the tissue of origin in patients with carcinoma of unknown primary[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2011, 17(12): 4063-4070.

[57] LAPROVITERA N, RIEFOLO M, PORCELLINI E, et al. MicroRNA expression profiling with a droplet digital PCR assay enables molecular diagnosis and prognosis of cancers of unknown primary[J]. Mol Oncol, 2021, 15(10): 2732-2751.

[58] SANDEN M O, WASSMAN R, ASHKENAZI K, et al. Observational study of real world clinical performance of microrna molecular profiling for cancer of unknown primary (CUP)[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2013, 31(15_suppl): e22173.

[59] POSNER A, PRALL O W, SIVAKUMARAN T, et al. A comparison of DNA sequencing and gene expression profiling to assist tissue of origin diagnosis in cancer of unknown primary[J]. J Pathol, 2023, 259(1): 81-92.

[60] STACKPOLE M L, ZENG W H, LI S, et al. Cost-effective methylome sequencing of cell-free DNA for accurately detecting and locating cancer[J]. Nat Commun, 2022, 13(1): 5566.

[61] ZHAO Y, PAN Z W, NAMBURI S, et al. CUP-AI-Dx: a tool for inferring cancer tissue of origin and molecular subtype using RNA gene-expression data and artificial intelligence[J]. EBioMedicine, 2020, 61: 103030.

[62] SHEN Y F, CHU Q J, YIN X X, et al. TOD-CUP: a gene expression rank-based majority vote algorithm for tissue origin diagnosis of cancers of unknown primary[J]. Brief Bioinform, 2021, 22(2): 2106-2118.

[63] CONWAY A M, PEARCE S P, CLIPSON A, et al. A cfDNA methylation-based tissue-of-origin classifier for cancers of unknown primary[J]. Nat Commun, 2024, 15(1): 3292.

[64] MASSARD C, LORIOT Y, FIZAZI K. Carcinomas of an unknown primary origin: Diagnosis and treatment[J]. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2011, 8(12): 701-710.

[65] MARTIN M, VILLAR A, SOLE-CALVO A, et al. Doxorubicin in combination with fluorouracil and cyclophosphamide (i.v. FAC regimen, day 1, 21) versus methotrexate in combination with fluorouracil and cyclophosphamide (i.v. CMF regimen, day 1, 21) as adjuvant chemotherapy for operable breast cancer: a study by the GEICAM group[J]. Ann Oncol, 2003, 14(6): 833-842.

[66] SCHUETTE K, FOLPRECHT G, KRETZSCHMAR A, et al. Phase Ⅱ trial of capecitabine and oxaliplatin in patients with adeno- and undifferentiated carcinoma of unknown primary[J]. Onkologie, 2009, 32(4): 162-166.

[67] HAINSWORTH J D, SPIGEL D R, BURRIS H A 3rd, et al. Oxaliplatin and capecitabine in the treatment of patients with recurrent or refractory carcinoma of unknown primary site: a phase 2 trial of the Sarah Cannon Oncology Research Consortium[J]. Cancer, 2010, 116(10): 2448-2454.

[68] SHIN D Y, CHOI Y H, LEE H R, et al. A phase Ⅱ trial of modified FOLFOX6 as first-line therapy for adenocarcinoma of an unknown primary site[J]. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol, 2016, 77(1): 163-168.

[69] BRIASOULIS E, KALOFONOS H, BAFALOUKOS D, et al. Carboplatin plus paclitaxel in unknown primary carcinoma: a phase Ⅱ Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group Study[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2000, 18(17): 3101-3107.

[70] GRECO F A, ERLAND J B, MORRISSEY L H, et al. Carcinoma of unknown primary site: phase Ⅱ trials with docetaxel plus cisplatin or carboplatin[J]. Ann Oncol, 2000, 11(2): 211-215.

[71] EL-RAYES B F, SHIELDS A F, ZALUPSKI M, et al. A phase Ⅱ study of carboplatin and paclitaxel in adenocarcinoma of unknown primary[J]. Am J Clin Oncol, 2005, 28(2): 152-156.

[72] PARK Y H, RYOO B Y, CHOI S J, et al. A phase Ⅱ study of paclitaxel plus cisplatin chemotherapy in an unfavourable group of patients with cancer of unknown primary site[J]. Jpn J Clin Oncol, 2004, 34(11): 681-685.

[73] HUEBNER G, LINK H, KOHNE C H, et al. Paclitaxel and carboplatin vs gemcitabine and vinorelbine in patients with adeno- or undifferentiated carcinoma of unknown primary: a randomised prospective phase Ⅱ trial[J]. Br J Cancer, 2009, 100(1): 44-49.

[74] HASEGAWA H, ANDO M, YATABE Y, et al. Site-specific chemotherapy based on predicted primary site by pathological profile for carcinoma of unknown primary site[J]. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol), 2018, 30(10): 667-673.

[75] TANIZAKI J, YONEMORI K, AKIYOSHI K, et al. Openlabel phase Ⅱ study of the efficacy of nivolumab for cancer of unknown primary[J]. Ann Oncol, 2022, 33(2): 216-226.